Maschere a Venezia

What mask will you wear to the Bal di Carnivale?

by Carol Wood, First published for the January/February 2014 issue of Finery

Put off that mask of burning gold

With emerald eyes.

Oh no, my dear, you make so bold

To find if hearts be wild and wise,

And yet not cold.

I would but find what’s there to find,

Love or deceit.

It was the mask engaged your mind,

And after set your heart to beat,

Not what’s behind.

But lest you are my enemy,

I must enquire.

Oh no, my dear, let all that be;

What matter, so there is but fire

In you, in me?

W. B. Yeats, The Mask

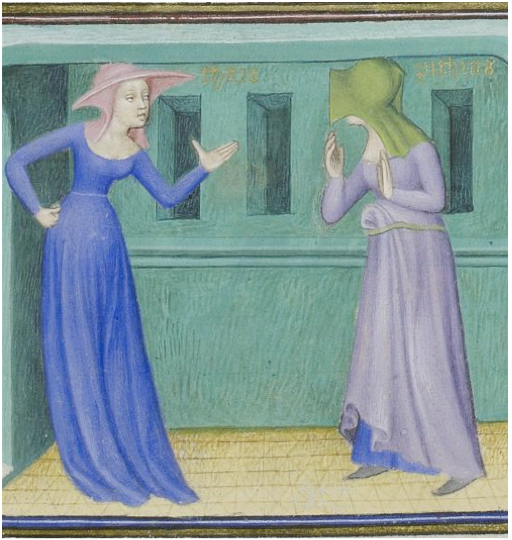

The man in Yeats’ poem wonders what his lover is hiding behind her seductive mask as have millions of revelers during Venice’s Carnival over the centuries. At the height of festivals in Venice’s history (mostly during the 18th century,) one could legally wear masks two thirds of the year. Depending on the decade, laws were decreed to regulate what time of day masks were allowed, even what gender could wear a specific mask. The rich, increasingly debauched, tradition of Carnival in Venice which found its roots in the 13th century declined precipitously five centuries later when the Republic of Venice fell to Napoleon’s army in 1797. The tradition found a rebirth, albeit only two weeks a year, in the early 1980’s. Today, the mask worn by most costumed revelers in Venice is the expressionless white full-face mask. Less usual, you can also see the generic half-mask that conceals only the area around the eyes. Humans must have a fascination with hiding behind a generic face, the face that melts into the crowd. Interestingly, this fascination is not unique to the 20th century, but was actually present for celebrants of earlier centuries as expressed by some of the masks here described.

There are a few masks commonly worn in 18th-century Venice during Carnival and at other times, and also some made famous by the Italian Commedia dell’Arte theater: The most widely worn mask was that which developed into a form of standard dress or uniform donned by Venetian nobility, “Bautta” or “Bauta.” This mask can be seen in most paintings depicting Venice in the arms of her beloved Carnival. Assumptions abound as to the origin of the mask’s name (see http://www.bluemoonvenice.com/en/venetian-masks/the-bauta in particular.) The mask itself was generally stark white with no embellishment. It covered most of the face from view, the upper lip of which jutting out so as to allow the wearer to converse and imbibe with ease. Those with means wore the Bauta covering the face, then the “volto” or “larva,” a black lace hood covering the wearer’s upper body skin and hair down to the waist. The Bauta and volto were usually held in place by a black tricorn hat. Sometimes, to hide even more clues to the wearer’s identity, a floor-length black cloak was worn. This was not only an economic equalizer, as anyone of any means was allowed to wear this mask, it was also a gender equalizer since not only a woman, but also a man in Bauta was addressed as “signora maschera,” or “lady mask.”

Also common and worn only by women was the “Moretta” or “Muta.” Originating in France, this popular disguise was first known in Venice as “Servetta Muta,” or “mute servant.” The name then merged into “Muretta”/”Moretta.” (Some say it got its name from Italian “moretta” meaning “small and dark.”) With its black velvet covered surface and only two small openings for the eyes, the wearer was forced not to speak because she held the mask to her face by gripping a small button mounted inside. Extremely erotic, the lady remained enveloped in mysterious silence with her face covered by this small oval mask, but revealed a beautiful décolletage and neck, unlike the less exposing Bauta with volta.

We may wonder why depictions of women revealing their breasts to potential customers typify the image of Venetian prostitutes. The roots of this form of advertising are tied closely to masks during this period. Homosexuality in 18th- century Venice was illegal, punishable by death, yet homosexual prostitution thrived during this time to the extent that it threatened female prostitutes’ business. One way in which male prostitutes skirted around the ban on homosexuality was to display their wares by dressing as a woman wearing a half mask that looked like a rosy-cheeked gal. By wearing the “Gnaga” mask, any man was merely acting a role, playing a part, which was completely legal and not punishable. The name derives from the way in which these men enhanced the charade as women by using a particularly harsh voice that sounded like cats screaming; “gnau” in Venetian means “cats.”

The fascinating “Il Mattaccino” costume didn’t always wear a mask to begin with, but its hallmark was brightly colored garments. This prankster was wont to pummel passersby, if possible the nobility, with perfumed eggs. The costume of Il Mattaccino evolved into that of a little devil with the horns emanating either from a headpiece or a mask. This character gets its name from the Italian “mattinate” meaning “mornings,” since these hoodlums stayed up to all hours looking for unsuspecting victims.

With its beginnings rooted in a very sad, but practical use, “Medico della Peste” (Plague Doctor) became a popular costume because of its frightening appearance. As early as the 13th century, doctors could be seen protecting themselves with an avian shaped mask. Emblematic of this full-face mask was the overlong beak that covered both nose and mouth. This beak had long slits extending down either side and was stuffed with aromatic herbs to filter the germ-laden air, similar to a gas mask. No longer out of necessity, but in keeping with the look, the Medico della Peste costume also consisted of a long stick with which to hold the afflicted at a safe distance, a full-length dark cloak, and a large black hat. The costume was meant to terrify spirits rather than keep yet-to-be discovered microbes away.

And then there were theater masks worn mostly by Commedia dell’Arte actors, but which also influenced masks worn by the common individual. Some of the better-known characters are below.

Donning the most authentically Venetian mask, the “Pantalone” character was penny-pinching and calculating, but also naively trusting. The mask had a very large nose with huge, bushy eyebrows.

Unlike the plague doctor, “Il Dottore” (the doctor) portrayed an expert in law or medicine and was either the caricature of pseudo erudite conceit, or a genuinely learned man who gave long, unintelligible monologues with puns aplenty. His was usually a half mask covering his whole forehead and nose and terminating in a mustache, but not covering his cheeks.

No Commedia would be complete without its “Pulcinella.” A loose-fitting white tunic and trousers with white peaked hat typify his poor, lovestruck hunchback. His mask is usually a black, half-mask with short, hooked nose, poofy cheeks, and furrowed brow.

“Arlecchino” (or Harlequin) and “Colombina” (also “Arlecchina”) wear the most iconic Commedia costumes: they are brightly colored solids in geometric patches outlined in black or white. Arlecchino usually wears a pug-nosed mask with drooping cheeks and a look of surprise. The only woman to don a mask in Commedia, Colombina may wear a very simple black half-mask.

“Zanni” (short for “Giovanni”) is the miserable servant with a thousand tricks just to get by. More than a specific mask or costume, this character is a persona that morphed into many aspects of characters like Pantalone and Arlecchino. However, typically he is portrayed in one of the better-known types of masks of the Commedia: very long, beaked nose, expressive eyes and eyebrows, and when full-face an exaggeratedly protruding chin or beard.

It is fascinating that Venetian masks hide their owners’ identities so very well precisely because, after having developed over many centuries, the iconicity of these masks is so prominent and admiringly confident. Wearer beware: The mask may be confident like the woman in the poem, but you may attract more than you bargain for. Thus, nosce te ipsum (know thyself)

References:

Mario Belloni, Maschere a Venezia: Storia e tecnica, 2006

Fulvio Roiter, Magic Venice in Carnival, 1999

Paola Scibilia, Venezia. Il Carnevale, 2006

http://www.delpiano.com/carnival/html/traditions.html

http://www.bluemoonvenice.com/en/history

Leave a comment