English, French, and Burgundian Women’s Bonnets in the 15th Century

One costumer’s exploration and recreation of historical headwear

by Cynthia Barnes, First published for the March/April 2014 issue of Finery

Before the heavily wired and beaded hoods so familiar from the portraits of Queens Catherine of Aragon and Anne Boleyn, there were softer versions. As seen in manuscripts, these hoods adorned the heads of women of various social levels, be they prostitutes or lady scholars or royal attendants. These hoods were produced throughout what were then France, Burgundy and England in the 15th century.

In English documentation, “hood” comes into common use after 1503. However, “bonnet” is used in English records to describe several variations of this headwear. English royal warrants almost often mention a matching or contrasting frontlet. Structural items such as “paste kerchiefs” were itemized separately in warrants. In England, the soft bonnet remained in use as court ladies’ mourning wear as late as 1503.

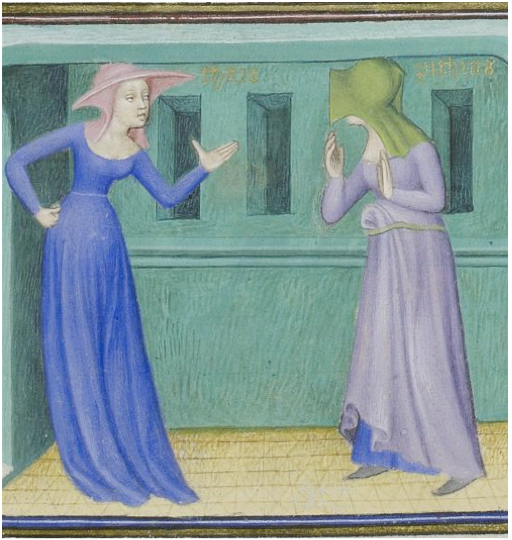

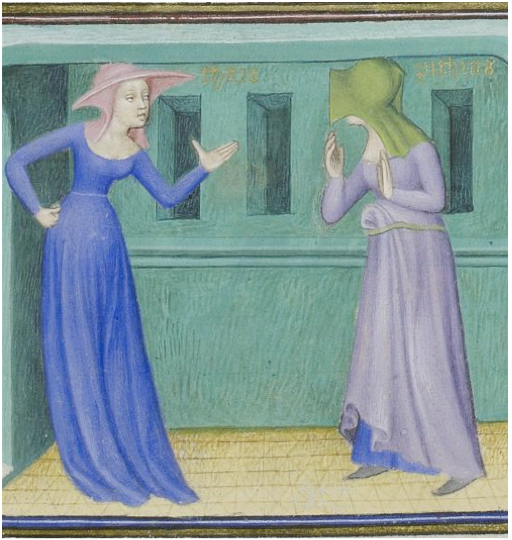

In its simplest form, the soft bonnet can be worn in a variety of ways: with the brim flipped forward or back, or folded and possibly pinned to form wide pointed “ears.” Both styles are seen in Figure 1. In my experiments, simply the weight and hand of the fabric is enough to make most of these shapes. However, the bonnet in Figure 2 appears to be wired, perhaps along the leading edge.

The liripipe of the work woman or scholar’s bonnet, if it has one, can be left hanging and is tucked into a belt or twisted into a topknot to keep it out of the ink pot, paint set, or away from scissors. The first bonnet I made was in plain black linen with no back shaping or gathers. The only style line is the jawline curve so that the back lies on the wearer’s neck and shoulders. It was extremely easy to make, wash, starch and wear. In addition, it was fully lined, but the back neck-drape was too heavy and lacked the characteristic fan-shape and folds at the back neck as seen in many Burgundian and French manuscripts.

The improved version in teal linen (Figure 3) has a liripipe and a “curtain,” which is the gathered drape seen at the back neck of so many Continental bonnets. I constructed the curtain from the offcuts. It is easy to experiment with pinning it into various shapes, as was the method used at that time. London silk women sold brass pins in quantities of 100s and 1,000s (even 10,000s for household of peers and royals). The arrangement and drape of women’s garments were regularly improved by the use of pins whether to secure a veil, close a partlet, or to fasten trimmings. This bonnet’s design is completely out of keeping with London finds from the 14th and early 15th century where English bonnets are heavily fulled wool, gusseted at the shoulder, not hemmed, and frequently dagged. Nor does my bonnet design concord with the late 14th century bonnets from Herjofnes with gussets front and back cut in one with the main body of the bonnet. Instead, my goal was to recreate the look seen in Burgundian and French illuminations.

In Figure 4, we see a side view of a very long and silly liripipe that, if allowed to drape, would probably fall to the woman’s knees. This side view also indicates a clear shaping for the brim and jawline. The choice of red is likely an artistic hint of the inflamed passions of the subjects. That said, other illuminations of virtuous women also indicate the use of red bonnets, as do supporting documents such as warrants from the courts of Henry VII and Henry VIII that list hoods of scarlet, tawny ingraine, graine, and murrey ingraine.

Bonnets with draped back and a frontlet turned back to frame the face

A final variation on the soft round bonnet shows no liripipe or point at all (see Figure 5). Here the front, side, and back views of similar bonnets are quite clear. The bonnet appears to have a separate pinned or partially sewn frontlet (decorative band) in gold. The gap between the back drape behind the head and the frontlet reveals the wearer’s neck. It is unclear whether the back drape is a separate pinned-on or sewn-on veil.

Towards the very end of the 15th century, and contemporary with the earliest forms of the “gable” or “doghouse” hood, this version of the soft round bonnet appears illustrated on English memorial brasses. A particular feature of interest in these gathered back bonnets is the contrast of color, texture, pattern, and fold lines. Carolyn Johnson conjectures that this bonnet is permanently gathered and “is often finished with a button” at the back to fill the gather hole. I tried a drawstring version on the theory that this would be more easily washed and laundered; however, when drawn up, the gaping hole at the back of the head has an unsatisfactory look to my eye. I added a button per Johnson’s suggestion, although there is no documentary or iconographic evidence for this style that I can find. Some 16th century hats do have button trims at gathers or pleats, and several “gable” hoods; therefore, the conjecture is not unreasonable.

It’s extremely difficult to determine what might be depicted on inscribed memorial brasses from the time. The rounded hood style runs remarkably late as seen in grave markers and memorials (Figure 6). It is unknown whether this represents an older woman who maintained the styles of her youth, or that the style was still popular in this locality, or whether the template used by the engraver was just outdated. A peek into contemporary documents such as wills, warrants, inventories, and private letters lend a few clues.

Of the reconstructions that I’ve done, the bonnet seen in Figure 7 looks most like the memorial brass images and is the most comfortable to wear. Johnson summarizes documents cataloging silk satins with a frontlet (decorative pinned-on trimming) of brocade, or tinsel. She also notes velvet bonnets with a frontlet of tilsent (a cloth of gold or silver). Additionally there are references in the warrants of applied and embroidered borders. I’ve substituted “cloth of brass” and “cloth of Mylar” in my demonstrations due to the expense and inaccessibility of cloth of gold and silver in suitable designs.

Bonnets with a pointed back

The next style of bonnet has liripipes at the tip of the crown; others appear to have a point. It is possible that its point is the result of a square cut, or possibly a deliberate shaping in an upward swoop. It’s also possible that some artists have depicted the liripipe flipped away from the face so that a fold in the fabric appears to be a point. Assuming that this point is deliberate, perhaps even a vestigial remainder of a tiny, little liripipe, I made two versions.

The fabric selection of grey silk satin with matching trim and black velvet (see Figure 8) are based on inventory listings given in The Queen’s Servants and Dress at the Court of Henry VIII. While this latter book seems wholly out of period for this survey of 15th century bonnets, the latter contains a few short sections on Henry VII’s reign with a review of the garments and wardrobes of his wives and mother. Johnson mentions that most English warrants issued for bonnets and frontlets also include a piece of silk sarcenet or sipers (a translucent linen in this period, not a translucent silk) that may be intended to construct veils and headrails.

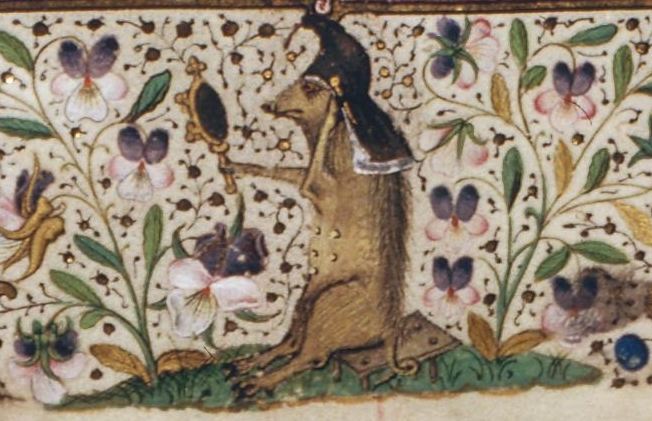

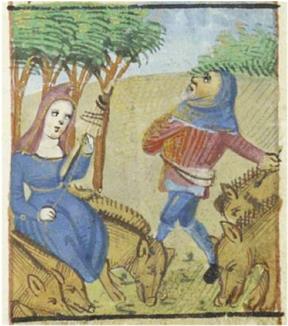

Below are examples of pointed bonnets that seem shaped differently than that with a liripipe. In the pointed ones, sometimes we see no shaping at the jawline. Instead, the design line that frames the face seems absolutely straight. In Figure 10, the bonnet is layered in possibly a veil or a lining. There is some amount of shaping at the back neck, but there’s no turned-back brim at the front. The pig’s bonnet and white under layers are secured at the temple with a gold, ball-headed pin. In Figure 11, the spinning woman wears a bonnet of similar design, but the brim is turned back brim around the whole of the face. The sideways lean of the perky point looks like mine, which is unwired.

In my black velvet pointed bonnet (Figure 12), the back neck drape was too tight, so I released it with a slit. I suspect it should have a back neck gusset inserted that’s more in keeping with the Herjofnes style bonnets where the back gore is cut as one with the main body of the fabric. The frontlet is not attached all the way down the front edge, leaving the distinctive gap at the shoulder and revealing the wearer’s neck. The lady’s bonnet in Figure 13 features the cutout jawline and turned back brim. There’s even a hint of a wrinkle at the fold line, possibly indicating a casual fold rather than a sewn-on brim or pinned-on frontlet. It also suggests that there isn’t wire or “paste” supporting the folded brim. My bet is that it’s just starch and the thickness of layered fabric that forms the turned back brim. In contrast, Figure 14 depicts a pointed hood with a possible sheer or translucent veil worn over the hood and under the frontlet.

Bonnets of the 15th century were varied in style and in the use of materials used in construction and decoration. These images and my samples are only a small number of many possible styles and color combinations depicted in artworks and noted in contemporary documents. All of the samples I produced are machine sewn, mechanically woven, using modern chemically dyed fabrics none of whom is period correct to the 15th century. Additionally, and equally inappropriately, acrylic velvet, Mylar, “cloth of brass,” modern silk pins, modern sizing and starch have been used in the construction and display of these items. Plainwoven linen is a good substitute for the looser, softer twill and tabby hand weaves discovered in London archaeological finds. From written English records, fur was a common though regulated bonnet lining. Acknowledging that I don’t live in a Little Ice Age but in California, I did not make a fur lined version. These bonnets are in no way “chapter and verse” perfect recreations. They represent only a preliminary, yet earnest, effort to reproduce a selection of 15th century bonnet styles given limited material evidence.

References:

Hayward, Maria. Dress at the Court of Henry VIII. Southampton: Maney Publishing, 2007.

Johnson, Caroline. 2011. The Queen’s Servants: Gentlewomen’s Dress at the Accession of Henry VIII. Tudor Tailor Case Studies, eds. J. Malcolm Davies and N. Mikhaila. Surrey: Fat Goose Press Ltd.

Malcolm-Davies, J., and N. Mikhaila. 2006. The Tudor Tailor. Los Angeles: Costume and Fashion Press, QSM Ltd.

Piponnier, F., and P. Mane. 1995. Se Vetir au Moyen Age (Dressing the Middle Ages). Paris: Biro.

Scott, Margaret. 1986. The Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries. Visual History of Costume. London: B.T. Batsford Ltd.

Ribiero, A., and V. Cumming. 1989. Accessories. Vistual History of Costume. London: B.T. Batsford Ltd.

Other Sources:

“Dress and Fashion Collection: Medieval-Tudor Collections.” Museum of London, 150 London Wall, London UK.

Exhibit catalog: Brocarts Celestes: Paintings from Le Petit Palais and Textiles from Musee des Tissus des Tissus de Lyon. Le Musee du Petit Palais, Avignon, 2005.

Leave a comment