A Legacy of Linen

by Betsy Hanes Perry. First published for the July / August, 2009 issue of Finery

Many costumers, having waited for years for the late Janet Arnold’s Patterns of Fashion 4, will have already either bought or checked out this book. This review is therefore an appreciation and an introduction for those lucky readers unfamiliar with the Patterns of Fashion series. I say “lucky” because you have hours of joy ahead of you.

Janet Arnold broke new ground in fashion scholarship. She treated surviving clothes as specific artifacts, with individual history and meaning, rather than as instances of trends. When she documented a piece of clothing, she gave what was known of its provenance, the materials and methods of construction, including later alterations, and, most revolutionary, scale drawings of the individual pattern pieces that composed the original garment. If you want to know exactly how a particular garment was made, Arnold is the gold standard.

For some years, her fans eagerly awaited Patterns of Fashion 4, a book on surviving 16th-and 17th-century linens and accessories. Arnold’s declining health prevented the book’s being completed. Jenny Tiramani, the head of design for the Globe Theatre, and the great lace historian Santina Levey, Arnold’s literary executor, have completed the manuscript with love and expertise. The patterns include 15 shirts, 9 ruffs, 11 “supporters, underproppers, pickadils and rebates,” 12 “bands, pinners, and tuckers,” 14 linen coifs and caps, 11 “drawers, boothose, and gloves,” and 15 smocks.

The book has a splendid 61-page introduction, 48 pages of which are in color, providing photographs of both artifacts and portraits. The color photographs are decorative and useful. It is especially wonderful to see the surviving embroideries in detail; a picture tells you so much more than “embroidered in honeysuckle pink.” There’s a very useful afterword by Tiramani on how to construct reproduction garments using the patterns, including detailed instructions on starching and setting ruffs.

What about the patterns themselves? Once again we meet the Sture family, assassinated in Uppsala in 1567; this time, we see an elegant linen shirt, both as it appeared in a portrait and as the shirt itself survives. The shirt layout is plain, and any costumer has probably built several variations on it; however, the detail of the embroideries and their placements is fascinating. This is true of most of the shirt patterns – although there are subtle variations on the cloth-conserving rectangular construction, the lace and ornamentation are the most striking and varied features.

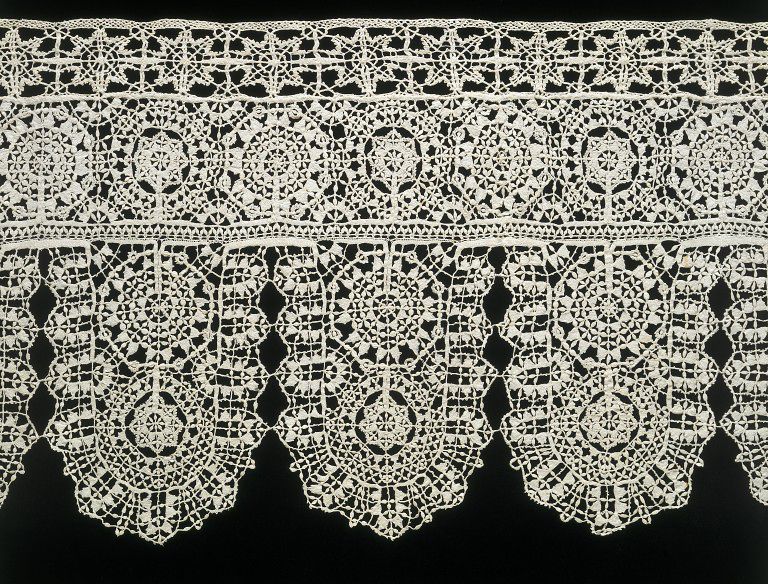

Scalloped border for collar or ruff in bobbin lace worked in linen thread, probably made in Genoa, 1630-1640

An inherent limitation of the book is that underlinen construction is not as complex as the construction of outer clothing; the scale drawings of ruffs do not have the same “Aha!” value as the elaborate doublets and bodices of volumes 1-3. Ruffs are, not surprisingly, built of long strips of linen, finished and seamed together; one ruff pattern is very much like another. The accompanying sketches of the finished ruffs are much more informative: “At the neck edge there are 600 [!] tiny cartridge pleats, each held to the neckband with a single stitch.” The scale drawings of the lace, however, are mesmerizing – I suspect Levey may have contributed these, but they could equally be Arnold’s work. Many of them are drawn to actual size. The careful sketches of the embroidery are also useful, although most are so small in scale as to require a magnifying glass. If I were trying to reproduce these costumes, I imagine that the lace sketches would be useful; for the embroidery I should prefer to consult the photographs in the front of the volume.

As in Queen Elizabeth’s Wardrobe Unlock’d, there’s a lot more to Patterns of Fashion 4 than the clothing itself. Interwoven with the descriptions of the individual garments are bits of contemporary commentary on costume: “In The Mooncalf, published in 1627, Michael Drayton satirized the dress of women thus: ‘In everything she must be monstrous: Her Picadell above her crowne upbears, Her fardingale is set above her ears.’ He was presumably comparing the large curved sets of her closed ruff supported on a large pickadil, with the ruffled flounces of a wheel farthingale skirt, and he conjures up the image of a woman wearing her skirt around the neck.”

Any costumer will probably enjoy reading Patterns of Fashion simply as a work of costume history. You’ll be applying this book only if you costume in the period (1540-1660) or if you’re particularly interested in ruff construction. Whether or not you ever build a Tudor or Jacobean outfit, you’ll enjoy reading the book for its scholarship and reveling in the photographs and drawings. Patterns of Fashion 4 is a worthy memorial, and reminds us of how much we’ve lost with Miss Arnold’s death.

Leave a comment