Imbibing Fashionable Waters

by Deborah Parker Wong, First published for the March/April 2013 issue of Finery

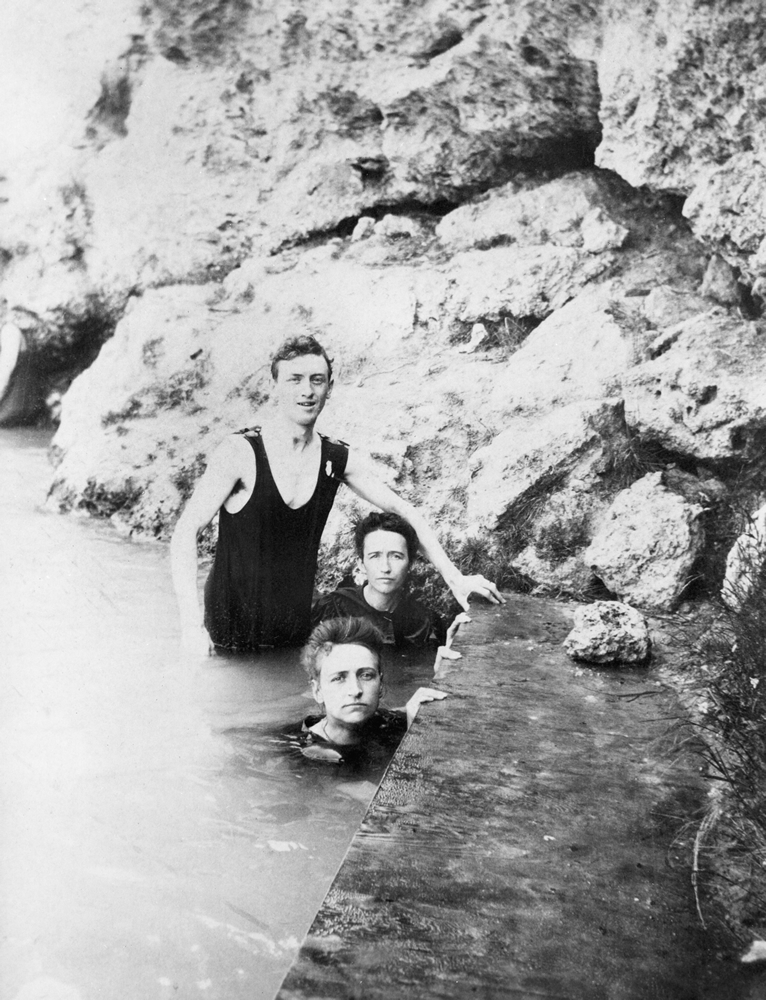

From sacred springs to the Roman baths, the healing power of water are found referenced throughout history. During the 18th and 19th centuries, “taking the waters” became a popular past time for the leisure class. Whether done at the advice of a doctor or simply as a relaxing retreat, by the early 20th century, the practice of imbibing and bathing in mineral waters (known as Medical Hydrology) was a recognized specialty of medicine in America. The varieties of waters included carbonated, creosote, pine, and starch baths in addition to galvanic and faradic treatments. However, less beneficial baths involved radium and radon, lithium, arsenic, mercury and other heavy metals.

Mineral-water therapy diminished with the passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act in 1907, but hydrology remained fashionable. Modern balneology (mineral bath therapy) is practiced in Europe, Japan, and Saratoga and Calistoga in the U.S.

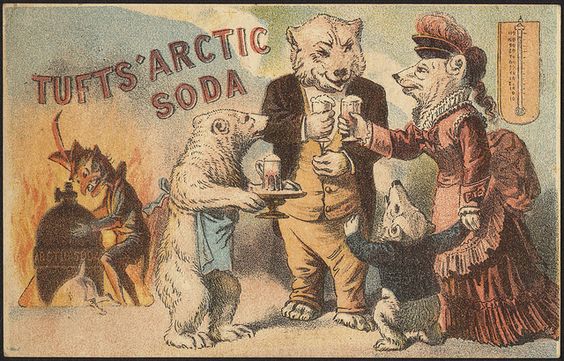

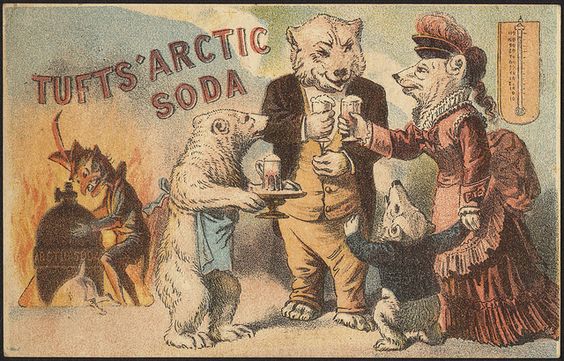

The Era of Gases

Mineral waters have long captivated our imaginations and soothed our ailments, but it was our fascination with naturally-sparkling mineral waters that inspired the invention of carbonated water and, with it, the soda fountain. From late 18th/early 19th centuries, English and French chemists sought to simulate the chemistry of natural mineral waters. This “Era of Gases” led to numerous discoveries including that of English chemist Joseph Priestley who, in 1767, generated carbon dioxide gas (C02) by pouring acid on chalk. Dissolving C02 in water created “an exceedingly pleasant sparkling water” Priestley later collaborated with Johann Jacob Schweppe in developing a device to create “aerated” waters for commercial sale in 1783. A decade later, Schweppes Company opened their first factory in London and it still endures today.

In the U.S. scientists began developing methods for the commercial production of carbonated water (commonly called club soda and seltzer water). In 1807, geologist Benjamin Silliman produced bottled soda water and opened an establishment for dispensing it. By 1809 a U.S. patent for imitation mineral water was issued to Joseph Hawkins. By mid-century, the bottling of naturally-sparkling mineral waters was a well-established industry in the U.S. While these were popular, they were costly to bottle and transport. There was no efficient, low-cost way to artificially carbonate water for mass consumption until British inventor John Mathews

created the first soda fountain device in 1832.

Mathews’ apparatus was a lead-lined tank where sulfuric acid and calcium carbonate combined to produce C02, which was then dissolved in a tank of water to “charge:’ The resulting carbonated water was dispensed through a tap and the soda fountain was born. Mathews sold bottling units and fountains to pharmacists, but manufacturing C02 was a risky business for the inexperienced. Eventually, entrepreneurs began to manufacture C02 in tanks and soda fountains quickly became part of mainstream American culture.

Flavored Soda Water: An American Invention

Unlike in London and Paris, where naturally-sparkling mineral waters were popular, flavored soda water was clearly an American invention. Pharmacies were the sole source of soda fountain beverages. Druggists used flavored soda water as a vehicle for liquid medicines and for dispensing nervines that contained caffeine, cocaine, cannabis, morphine, opium and heroin. These energizing drinks quickly replaced the morning cocktail or nightcap until their addictive ingredients became illegal in 1914 when the Harrison Act banned the use of cocaine and opiates in over-the-counter products. By that time, consumers were already hooked on the soda fountain.

Popularity of the soda fountain surged when Prohibition was enacted in 1920. After repeal in the 1930s, adults abandoned the soda fountain until WWII, when alcohol was again harder to come by. By the 1960s, bottled soda pop was available from vending machines and pharmacies closed their soda fountains. Not surprisingly, the renaissance of classic cocktail culture has reawakened an interest in phosphates, lactarts, and tinctures to create classic soda fountain beverages from this bygone era.

Taste of a Bygone Era

Classic, non-alcoholic fountain sodas range in flavor from sweet to bitter and rely on an arsenal of unfamiliar but delicious ingredients that are unknown to American consumers. In the 1950s there was a shift in consumer preferences away from the dry, tart, and fresh flavors of fountain drinks like phosphates and lactarts due to the growing popularity of Coca-Cola and bottled sodas. Anyone born after that time missed experiencing these beverages that emphasized flavor, balance, and texture over the cloying sweetness of today’s soft drinks. Both soda fountains and ice cream parlors served phosphate sodas that have the same pH as fresh squeezed lime juice. Invented in the 1870s, these sodas had a dry, tart flavor that distinguishes them from other sodas made with citric acids. Cherry, chocolate, and lemon phosphates were very popular in the late 19th-century. Today, cola soft drinks still use phosphoric acid in their formulations while other sodas use citric acid.

In the early 1800s, the Avery Chemical Company created lactart as a healthy, natural acid for flavoring beverages. A dilute form of lactic acid (commonly found in yogurt and buttermilk), it has a much more subdued tang than citric acid. With no dairy taste on its own, it works well with dairy products.

Whether they include ice cream or stand alone, balanced, fresh and utterly intriguing is the best way to describe the phosphates, lactarts, and fountain sodas that are straight from the classic soda-fountain era.

Leave a comment