Women’s Institute of Domestic Arts and Sciences

by Carol Wood, First published for the January/February 2010 issue of Finery

Sewing has waxed and waned in the hearts and homes of American women over the past century. The home sewing machine was available from the 1850’s and considered an integral piece of furniture to a well-appointed home. Despite these machines making home garment production even easier, the interest in learning to sew and home garment production dwindled. As one might expect, this was due to issues of time and money.

During WWI, many women contributed to the war effort as well as household finances by working outside the home, making time for sewing scarce. In the late teens and early 1920’s, fashions became less form-fitting and cheaper to mass produce, which meant less of a strain on the household pocketbook when purchased ready-made. Dwindling interest in home sewing had a large effect on manufacturers and retailers, so many industries took steps to resurrect that interest.

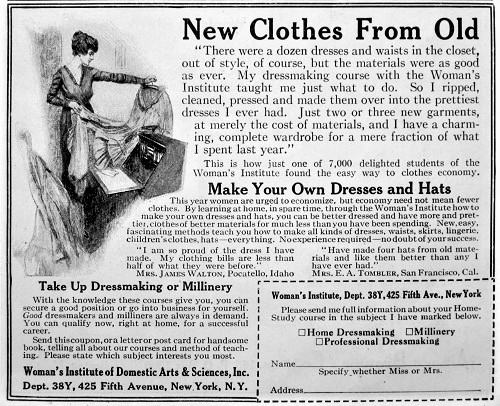

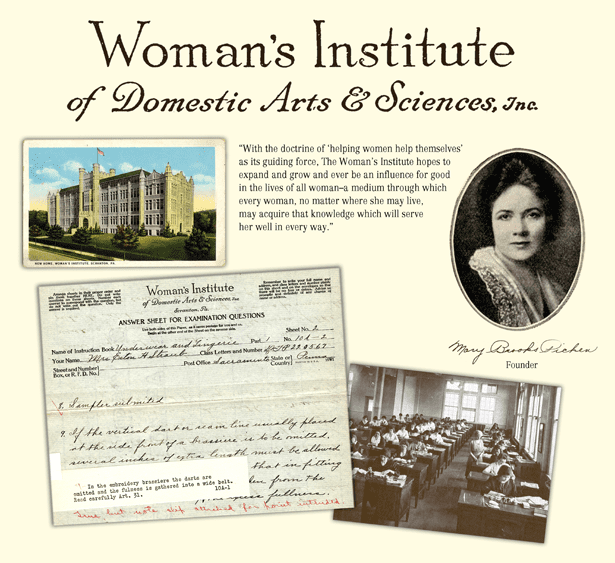

The Woman’s Institute of Domestic Arts & Sciences was just one of many such efforts. The Woman’s Institute was a subgroup of the International Correspondence Schools of Scranton, Pennsylvania (ICS) that educated coal miners in mine safety from 1891. The success of ICS courses depended upon excellent materials, organization and savvy marketing. From 1916 until the late 1930’s, the Woman’s Institute fostered those successful attributes of the first ICS course, especially marketing. Not only did its advertising speak to women’s need to be careful with household finances and to the possibility of creating clothing of one’s own preference and better fit, but most importantly it promoted the traditional American concept of womanhood and domesticity through sewing. Course booklets and magazines reinforced these values with statements about how home dressmaking could improve marriages and save families from the shame of shabby dressing.

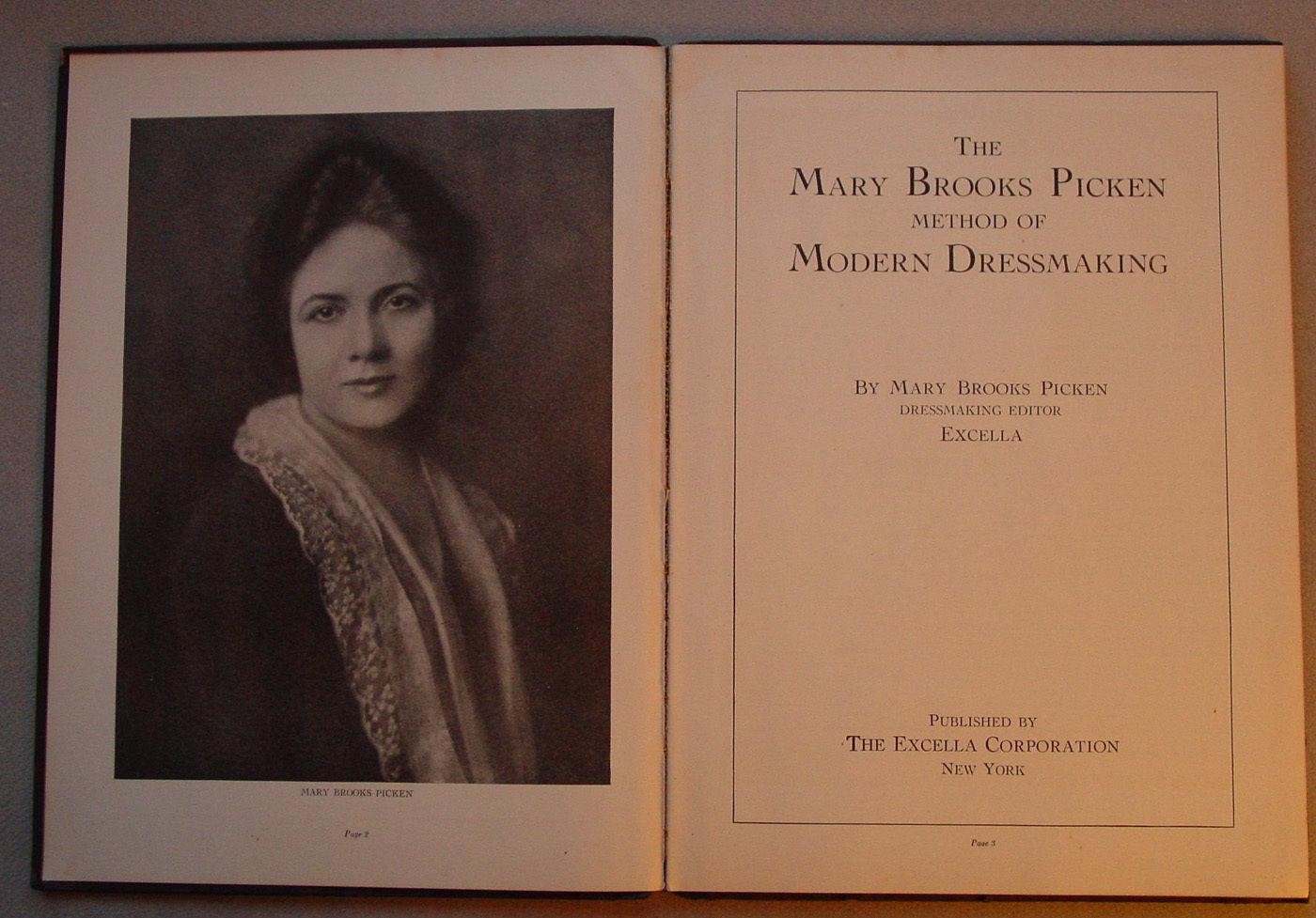

The star of the Woman’s Institute was its founder, Mary Brooks Picken, a longtime seamstress. In 1914 she began writing the curriculum and instruction booklets for the International Correspondence School dressmaking course. Picken was a prolific writer, authoring 96 booklets and books on sewing, fashion, and interior design. After the Woman’s Institute shut its doors, she wrote instructional books for Singer and the Pictorial Review, as well as a fashion dictionary which is still in print. She taught at Columbia University and founded numerous fashion-related committees and institutes still influential today. The cost of the course was quite reasonable since many women were able to do piecework or one-off commissions during the course and after graduation. One Application for Membership lists the basic dressmaking course at just $44 in 1928 and the ingenious installment plan hooked many! A student could start for as low as $3-$5 per month, and if she had registered for dressmaking plus tailoring, her deposit of $10 guaranteed the loan of a dress form in addition to the normal course materials.

The student was sent her first packet of instruction booklets, answer sheets, pattern paper, tailor’s square, tape measure, garment blocks, and lesson sequence. She completed the stitching exercises and answered examination questions which she sent in to be graded and returned by “instructors”. After successful completion of all required lessons, the student received a beautiful certificate of graduation.

Being a student of the Woman’s Institute meant she had access to a network of people to help her succeed. She could send in questions on Woman’s Institute stationary with pre-printed envelopes and receive hand-written “instructor” responses. She could join one of the clubs or found her own and report on the progress the club was making. Through the Woman’s Institute, she could purchase fabric, tools, and notions at greatly reduced prices and subscribe to magazines only available to registered students.

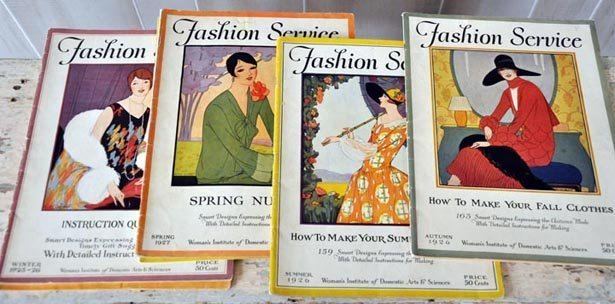

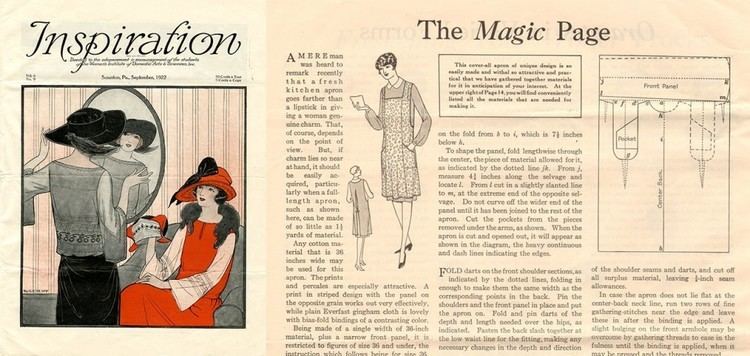

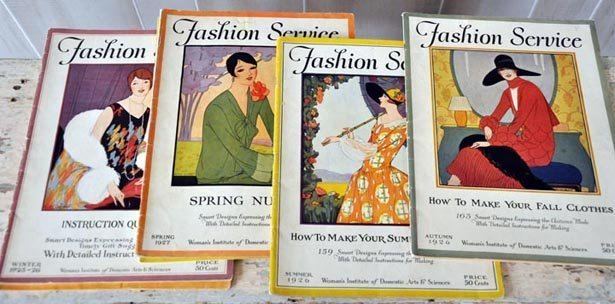

The magazine Inspiration (at $.05/copy) was printed from 1917-1927 after which it merged with Fashion Service, (1920-1932.) In order to keep students abreast of trends in fashion and the Woman’s Institute’s offerings, these magazines served not only as a visual inspiration for students referencing lessons in course booklets, but also as one of the many clever marketing gimmicks. These magazines built a community of dressmakers, printing letters, announcing accomplishments, and announcing changes in fashion and the Woman’s Institute. The material covered in the course booklets, books, and magazines is a wonderful resource for women’s and children’s clothing as well as sewing and drafting techniques.

Some of the booklets include isolated lessons, like in Essential Stitches and Seams or Aprons and Caps. However, most lessons are cumulative and require doing exercises in sequence. The language is also a product of the time and sometimes rather difficult to follow, but there are many photos and sketches to help. I found that, because of the language and steps omitted, just understanding the special publication on the one-hour dress took more than an hour before embarking on the project. Estate sales and the internet are great resources for these materials for purchasing or even reading electronically. Prices vary wildly and range from $10 to $25 for a booklet or magazine.

Millinery course booklets were the least published and are now the most sought; recently, a complete set of 12 millinery booklets went for over $600 on Ebay! Since booklets kept up with the times and were revised and republished over the years, they are a great source of visual and technical inspiration. Underwear and Lingerie, for example, was revised and published four times between 1916 and 1922 alone, including era-appropriate garments and techniques. Despite style changes, the course’s foundation of stitches, drafting patterns, good use of resources, and how different textiles behave are a constant for any era.

Editor’s Note: Those who wish to see a sample of one of these publications will find Secrets of Distinctive Dress available as a free download from Google Books.

Leave a comment