Strut Your Tut

Eastern Influences on 1920’s Fashion

by Carol Wood, First published for the March/April 2011 issue of Finery

The 1920s was characterized by exploration, experimentation and invention. This holds true for fashion in particular: No more restrictive corsets, experimentation in dress was socially acceptable, and more women earned money to afford the new fashions. Not only did hemlines run up and down the leg during this decade, but styles ran the gamut across cultures and eras. By gum, Eastern exotic was the thing!

Japonais and Chinoise styles had been appearing in fashion for quite some time. What woman didn’t own a lounging pajama with Chinese collar for in-home entertaining? Or a kimono to toss over her negligee? Newer, however, were influences from the Near East: Egypt, Persia, Arabia, Turkey. From the Thebaid desert to the gardens of Shiram came design inspiration that would take root both in cut and fit, but also in rich palates and bold, exotic patterns.

By the end of World War I, people were starved for new and exciting design. As the new decade wore on, money began to flow freely into both screen and stage entertainment allowing for lavish, exotic sets and costumes. Exemplary was 1921‟s “The Sheik” with Rudolph Valentino with his turban and painted eyes. That film came on the heels of 1917’s “Cleopatra” in which Theda Bara’s gown was made of $1,000 per yard fabric – it’s just that “Theda seemed to be wearing only ten cents‟ worth,” noted by her biographer, Ronald Genini. It was rumored that publicists sent out press releases claiming Miss Bara was the daughter of an artist and an Arabian princess, and that “Theda Bara” was an anagram for “Arab Death” – how alluring! 1921 also boasted “The Queen of Sheba” with Miss Bara and “The Young Rajah” with Valentino. Cinema audiences couldn’t get enough of Valentino dripping in luscious silks, so they were treated to “Son of the Sheik” in 1926.

No stranger to settings in Near-flung regions, the stage was a prime arena for feeding the public’s newfound passion for the exotic Near East. Starting nearly two decades earlier, Leon Bakst championed exotic set and costume design for the ballet in Paris: “Salomé” in 1908, “Cléopâtre” in 1909, and “Shéhérazade” in 1910, to name only a few. Patrons of the Ballets Russe ate up the exquisite Vaslav Nijinsky and Ida Rubenstein, both in balloon pants and draped in pearls.

Evolving simultaneously, entertainment and high fashion dallied in the new aesthetic. By the late teens and 1920s, gone were the gaspingly corseted figures giving way to a fashion that would reveal the female form: figure-skimming silhouettes as well as legs, lots and lots of legs. Bloomers saw their debut on the stage in 1838 when the French actress Rachel wore authentic Muslim women’s trousers as “Roxanne” in “Bajazet,” then bled into off-stage wear when another actress was seen wearing pantaloons in 1843. These rare incidents don’t compare to the barrage of “Turkish” trousers worn in the boudoir, on the stage, and – gasp! – in public in the 1920s.

There were two high fashion designers who dipped their design quills into the Near East pot of new sensations: Paul Poiret and Erté. Poiret, a Paris native, grew up in the heavily tailored, highly constrictive era of the late 19th century. “The King of Fashion,” as he is sometimes referred to, is credited with abolishing the corset (we had to blame somebody!) and bringing the art of draping into the forefront of fashion. His Parisian fashion house of the teens employed the language of orientalism to bathe women in “lampshade” tunics, “harem” pantaloons, and all manner of drapes with tassels.

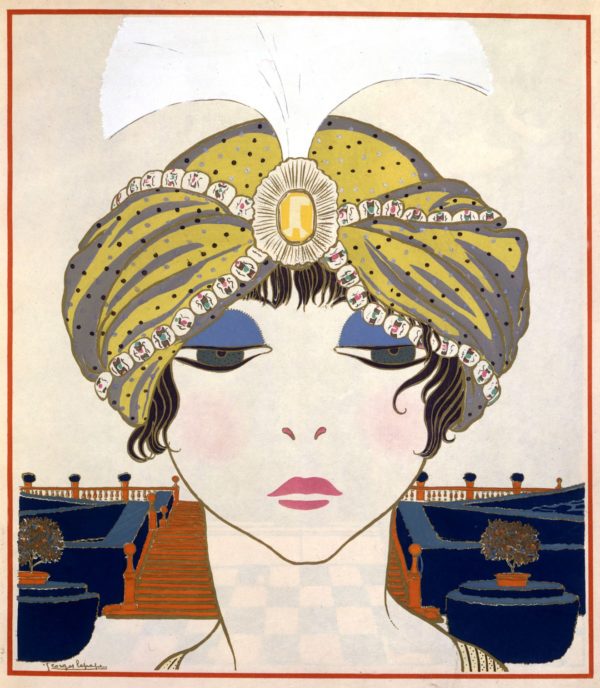

Then came the Russian-born French designer, Romain de Tirtoff (initials R. T. – get it? Erté!), who moved from St. Petersburg to Paris in 1915 at the sweet age of 18. He was awash with the new Art Deco movement, a shift away from swirly pastel naturalistic design of Art Nouveau and into bolder hues and shapes. Vivid color from the Near East was irresistible in Erté’s designs for turbans, “Turkish” trousers (or “Harem pants”), long cutaway vests, and everything shimmering with metallics and jewels.

Travel played an enormous role in spreading this new fashion craze. That is, travel to the Near East by Europeans and Americans. They journeyed in droves on the Orient Express from France all the way to Turkey filling their cameras and their memories with images of contemporary fashion on the streets of Istanbul. Then there was the discovery of King Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922 and “Tutmania” was born. Names for colors went wild with the likes of Coptic, Sakkara, Egyptian green and carnelian. Motifs stylizing ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs adorned everything from cloth to handbags to “mummy” powder compacts! There were cheap imitation “Cleo” earrings, lotus motifs on footwear, and scarab everything: broaches, earrings, necklaces, etc.

And then there was the common woman. Those not among the elite who traveled, consumed exotic entertainment, and purchased high style were exposed to these innovations through tabloids and film. Near East exoticism in fashion trickled down to street apparel in the form of cheap imitations of high style and elements in affordable clothing. While a working girl might not wear a turban to the factory or behind a type writer, she might wear bolder shades, the cloth might have an exotic print, or she might don a scarab brooch on her deep crimson wrap-over coat.

The shift from tailored garments over constrictive corsets to clothing more practical for movement and care occurred simultaneously with, perhaps even to some extent as a result of, the West’s incorporation and interpretation of Near Eastern design elements. The early 20th century was a time of world exploration on a previously unheard-of scale which prompted self-exploration and reevaluation of what was expected and what could be risked – from a clothing perspective. Fashion has always been a vehicle for pushing the boundaries of acceptability, decency, and expression of self. Near Eastern design made a bold impression on the world and the world of fashion of the 1920s.

Leave a comment