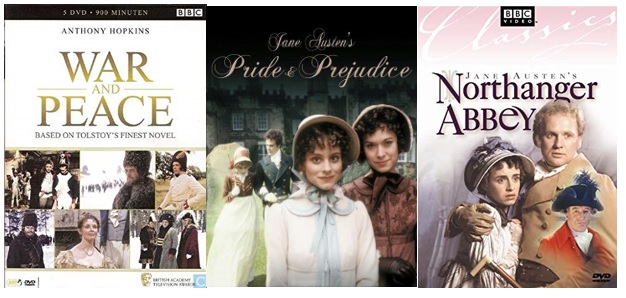

Regency Costumes from the BBC Television Productions

A review of some productions from the 1970s and 1980s

by Sally Norton, First published for the May/June 2003 issue of Finery

The British Broadcasting Corporation is known for high production values. Programs such as Elizabeth R, Poldark and Lillie accurately recreate a past time and place. The costumes are a major contribution to the overall feel of a historic production.

Costume design for television has a definite set of requirements and limitations. The costumer must consider lighting and color; some colors wash out on film, some fabrics simply do not light well. The costumer must understand the director’s vision, meet the producer’s schedule, stay within budget, use colors and fabrics that light well, are complimentary to the actors and appropriate for their characters, and finally, create designs that can be made by the available workers.

The costumes from Pride and Prejudice, War and Peace, Northanger Abbey, Sense and Sensibility and Vanity Fair all display the charm of dress in the Regency era period and the fine workmanship in the BBC costume shop. The detail in these costumes is extraordinary.

Regency dress had its origins in the late 18th century. English portraits from the 1790s feature unpretentious white dresses with long sleeves, a slightly raised waistline, and colored sashes. Both men and women abandoned their powdered wigs. In the early 1790s women wore their hair in loose curls. By the late 1790s, styles were very different, reflecting a classical Greek influence.

David was the outstanding French artist of the decade. His ideas and painting helped to persuade people that ancient Greece was the finest artistic expression. The English upper classes and the growing class of moneyed tradesmen were already interested in the latest fashion which happened to be, classical art.

The style was all the more acceptable because it differed so radically from the artificial, cumbersome, restricting fashions of the hated French court. By the late 1790s the public, both in France and England, was ready to celebrate and loose, elegant clothing was perfect. This movement set the fashion for the next 25 years. We’re still borrowing these ideas today.

The costumes for the 1972 production of War and Peace were designed by Charles Knode (he also designed the costumes for the Mel Gibson film, Braveheart). In the scene when the Rostov family flees Moscow, Natasha wears a burnt orange gown and adds a wool challis pelisse in a brown and tan floral print.

The first thing you will notice about this dress is the complete lack of waistline. The skirt falls straight in front. The general silhouette of this gown is column-like and, while it falls close to the body, it is never tight. The fullness is concentrated in the center back where it is gathered. It has a demi-train. The sleeves are long, well below the wrist, and tight. The trim is repeated on the upper sleeve, which is further accented by a puff made of cream-colored voile. The same cream voile is sewn as an insert at the throat.

We usually think of sheer muslin dresses during the Regency but, Natasha’s heavy velvet is much more suitable for the Russian climate. In England, velvet was a popular choice for a pelisse.

The Sense and Sensibility (1981) costumes were designed by Dorothea Wallace. Elinor Dashwood’s pale green dotted swiss day dress is exactly the style of dress we associate with the Regency era. Elinor wears this dress in three scenes, all of them taking place at home. The dress is trimmed with a band of brown velvet ribbon at the empire waist and a small fringe of cotton lace across the front of the shirred bodice. The lace is repeated, trimming the edge of the 3/4-length sleeves.

This dress is a fine example of choosing a modern fabric (dotted swiss cotton) to meet theatrical needs. It is extremely difficult to light muslin; it becomes almost transparent and the dress disappears. (Mrs. Dashwood would never have allowed Elinor and Marianne to wear invisible dresses!) White dotted swiss cotton is a delicate fabric with good movement; it has more hand and weight than muslin and is a reasonable substitute.

The neoclassic style took its inspiration in part from the excavations in the mid-eighteenth century of ancient sites at Pompeii and Herculaneum. All things of ancient Greece were looked on as ideal. Painting, architecture, sculpture, furniture, and fashions all fell under the spell of the craze for the antique. Muslin was the fashionable material for day and evening, though more elaborate materials began to appear about 1809 for evening wear. The “Ladies Monthly” in June 1802 declared that dresses were now so thin they could be sent by the two-penny post.

The sleeves are sometimes set in and often have shirring, as they do in this dress. The incredibly narrow back section necessitates a sleeve design totally different from the shape of sleeves today. These dresses are notable for their utter simplicity. Eleanor wore only pearls. No doubt, Mrs. Elton would approve.

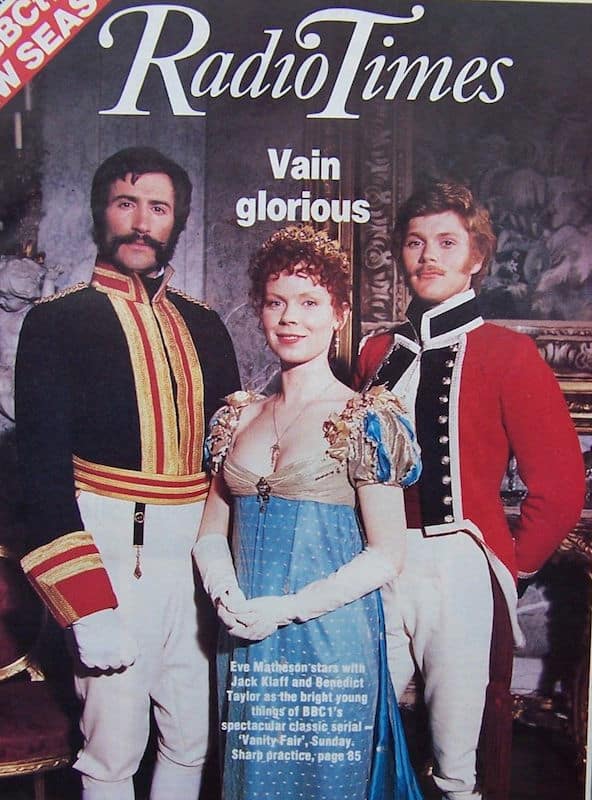

The dresses from the 1987 production of Vanity Fair are remarkable for the extensive handwork in the embellishment. The costumes were designed by Joyce Hawkins. In Part 8 of Vanity Fair, prior to the famous battle scene, an unnamed Englishwoman is seated in a hotel lobby with other English civilians. The woman is wearing a wonderful blue-grey dress made of wool crepe and trimmed in pink silk satin.

The empire waistline is emphasized by a band of blue braided cord. The bodice wraps in front forming a V neckline. The neckline is edged with pale pink silk satin piping. The piping is repeated on the sleeves. The sleeves are quite wonderful. The upper sleeve is cut in two pieces sewn together in an overlap thereby forming a petal-like cap. The petal edge has the same pink satin piping. The under-sleeve is long and straight. The wrist has a small fringe of delicate cotton lace. The outer side of each long under-sleeve is decorated with pink satin in a criss-crossed pattern. In France, the cross-binding pattern suggested the trussed victims carried to the guillotine; however, this grim association was gradually forgotten because cross-binding is an attractive and fairly simply pattern for decoration.

All of the trim on the sleeves and skirt is sewn by hand. One piece of pink trim has been laid down and then sewn carefully, turning it and forming the right angle cross-binding pattern. Every corner is a separate fold and stitched separately. This trim is even more extraordinary when one realizes this dress is worn by an extra in a crowd scene. Amazing.

Kitty Bennet’s ballgown from the 1980 production of Pride and Prejudice displays the same attention to hand-work and detail. The Pride and Prejudice costumes were designed by Joan Ellacott who also designed Upstairs, Downstairs (1971-1975) and The Lady and the Highwayman (1989). She received an Emmy nomination in 1977 for her costume design for Madame Bovary (also for the BBC).

Kitty wears her pale blue ballgown to the Meryton Assembly and the Netherfield Ball. The underskirt is dark teal silk satin. The entire dress is covered with a layer of white lace, thereby creating the pale blue color. A light blue velvet ribbon trims the waist. A 1-1/2 inch row of white cotton net fills in the décolletage; it is gathered up with a cord. The same net is used for the under-sleeve of the short, puffed sleeves. Two sections of lace lined with blue satin are attached to the top of the net sleeve for an petal-like over-sleeve.

The hem of this gown is a work of art…and fine sewing. First, three rows of light blue velvet ribbon are sewn by hand on the lace in horizontal bands. Then, a 2 inch piece of same lace used in the overskirt is attached and woven over and under the top and bottom bands of ribbon. The weaving process continues all the way around the skirt, forming a large cross pattern. Next, small sections of blue velvet are cut and used to wrap around the center of each lace cross; thereby, creating a design suggesting a chain of bows. All of this is done by hand and none of it shows up onscreen.

Nicholas Rocker designed the costumes for the 1986 production of Northanger Abbey. Austen purists are divided on liberties taken in this production but, the costumes are very good. In the carriage ride with John Thorpe, Catherine Morland wears the Regency modification of the 18th century Caraco jacket. In the Regency era, this garment evolved from a rather plan, every-day, house jacket into a stylish, feminine version of the new gentleman’s tailcoat.

Catherine’s jacket is light grey silk with a subtle orange pattern and is trimmed with 112-inch orange satin seam binding. The jacket is lined in pale orange which is on view in the rear folds of the jacket ‘tails’. The jacket is snug across the upper torso and flares into a half-peplum (or ‘tails’) formed by deep pleats in the center back. The sleeves are tight and can be short or long. The back seams are designed to give the impression of a very small back. Catherine wore this jacket over a white cotton gown and with all the fashionable accessories of the day: bonnet, gloves, reticule, and parasol.

Catherine might have needed her parasol as protection against the advances of Mr. Thorpe but, she escaped with only a reckless carriage ride. Longer parasols doubled as walking sticks. Small parasols often matched the color of a gown or pelisse. In the novel Sanditon, Mrs. Parker tells her husband, “I will get Mary a little parasol, which will make her quite as proud as can be. How grave she will walk about with it and fancy herself quite a little woman.”

Leave a comment