Notes on the Chinese Cheung Sam

by Mercurio Ekaterin, First published for the November/December 2004 issue of Finery

Although often thought of as a quintessentially traditional Chinese garment, the Cheung Sam (aka Qi Pao) is primarily a 20th-century evolution from the Manchurian banner gown.

At the turn of the century, the two-piece, loose-fitting shirt and trousers/skirt combination was still common alongside the one-piece banner gown. The earliest incarnation of the cheung sam reduced the voluminous sleeve of the Manchurian era as well as simplified its elaborate embroidery.

Along with greater civil and social liberties, the adoption of this garment released women from the tradition of binding breasts and upper arms. As a democratic influence, it became increasingly accessible and was worn by women of all social levels.

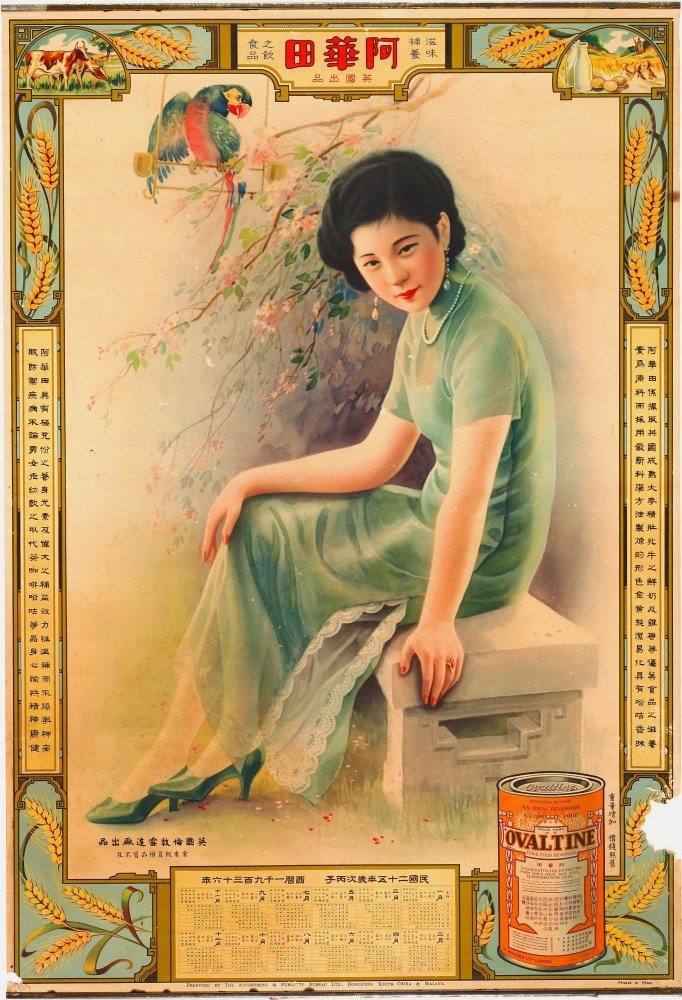

Early incarnations of this garment were unfitted, falling from the shoulder to an ankle-length hem. Sleeves were generally cut as one extending from the dress fabric, resulting in distinctive shoulder creases when worn.

Edge decoration had simplified from the Qing dynasty’s wide embroidered tape, of which a myriad of styles and designations were codified, to a narrow piping, typically constructed of starched silk, in various colors, multiplicity of rows, and even designs similar to soutache.

Frog type closures began at center neck, crossing the front and continued at right side seam, sometimes extending fully to hem. These were fabricated from the same material as the piping but were wired and sometimes stuffed in contrasting colors to form intricate knots and motifs matching the pattern of the fabric. Snap closed and zippered right side seams gradually replaced the extended frogs.

The cheung sam was made from a large range of materials including cotton, organza, silk, velvet, and calico. Heavier brocades and intensive overall embroideries were popular beginning mid-century.

Some versions of this garment were interlined with silk padding for added warmth. Other versions may be found fully lined or intended to be worn with a contrasting slip. Scalloped or laced edges in the underdress were also popular as, when seated, part of the back hem may be exposed, revealing the slip.

Patterns were not limited to florals as plaids, paisley, and Art Deco geometric prints were widely used.

By 1927, hemline had risen to about calf level. During 1928, the hemline rose dramatically to two inches below the knees and shifted from season to season thereafter.

At the same time, the length of sleeves also varied from long to elbow length to short cap sleeves. Their width, however, shrunk steadily from the pagoda sleeve inspired by the banner gown. In 1933, movie star Gu Lan lun began the trend of slits at the side seams. At the time, they extended upwards to the lower thigh. Two years later, the slits began to lower in conjunction with the dropping hemline, which was at floor length. The inconvenience of this fashion forced the hemline to rise.

The reputation of Shanghai cheung sam makers at this time was akin to Parisian designer fashions. A typical dressmaking shop was very small, headed by a master with two to three apprentices, specializing in hand sewing. There were up to over 2,000 independent dressmaking shops at the height of this fashion in Shanghai.

By the 1940s, wide, elaborate piping became almost completely obsolete, and hemlines remained slightly below the knees. The cheung sam’s evolution was stunted by shortages and social instability of the ’40s. A gradual conversion to western-styled dress for everyday wear continued.

In mainland China, the cheung sam became a symbol of decadence after the Communist Revolution of 1949 and was even banned during Cultural Revolution. Outside of the mainland, the early ’50s revived custom-tailored cheung sams as a form of day-today business attire for women. Its hemline rose to somewhat scandalous heights and became curved for an even more fitted silhouette.

By the late ’60s, tailor-made clothes became an expensive extravagance whilst ready-to-wear western garments flooded the market. The number of specialized tailors dropped over one-third and some broadened their trade to include western-styled garments.

The tailor-made cheung sam became increasingly a formal garment and was unable to compete with off-the-peg, standard-sized versions.

On the other hand, a much-simplified version remained in daily usage, uninterrupted from the tum of the century in some secondary schools as girl’s summer uniforms.

References

Clark, Hazel. “The Cheung Sam: Issues Of Fashion and Cultural Identity .” China Chic: East Meets West. Yale University Press: New Haven. 1999

Shanghai Online. “The QiPao in Shanghai.” Shanghai. 1996-2004.

Dressmakers. “Fashion After the Republic.” Taiwan. 2004.

The Academy of Chinese Studies. “History of Chinese Fashion.” Hong Kong. 2002.

Leave a comment