Modern Times: Changing Society 1900-1930

by Sally Norton, First published for the July/August 2003 issue of Finery

The life process is essentially social from the start. Throughout our lives we affect, and are affected by, many people. During the first quarter of the 20th century, society in the United States went through a gradual, but astounding evolution.

The forces affecting these changes were varied: education, employment, travel, women’s suffrage, a world war and the arts. Any of these would bring about some change, but the combination of some much in so short a space of time was remarkable.

The 20th century began with the Edwardian era; a time that seems far removed from stylish couples and their spiffy automobiles in the 1920s.

In the summer of 1900, fashion magazines were filled with gowns of semitransparent materials. The long skirt, slightly trained, was of inestimable value as a means of giving the appearance of height. This was especially desirable as the ideal female figure was tall, slender and graceful.

The 1910 afternoon ensemble has less embellishment than the Edwardian lady wore in 1900. It was a trim, comfortable outfit. Shirtwaists and tailor-mades attained dominance over the frilly, beribboned dresses.

In 1910 the future had arrived and it was to be owned by educated women who raised their skirts up off the ground and stepped out into the working world. Young women led a more active life and sought comfortable clothing for walking, hiking, bicycling and other sports. In the early years of the 20th century, the general populace developed a keen interest in healthful living.

The benefits of taking the waters at a spa had long been appreciated in Europe, but the idea only recently took hold in North America. Particularly in the Eastern seaboard, numerous establishments opened among the green hills of the countryside. All of them offered exercise programs, lectures, healthy diets, and a variety of social pleasantries such as afternoon tea and social dancing.

Most popular during the mild weather, the clothing worn at such establishments followed the current trend towards comfort and practicality — albeit accompanied by a large hat!

Over a period of several months between 1912 and 1913, Mrs. Eleanor Mather wrote a column for the ladies magazine, The Modem Priscilla. Her topic was ‘Exercise and Its Proper Relation to Health and Beauty’. Mrs. Mather explained the popular views held on exercise and fitness: “The woman who is neatness itself in person and dress, and whose exterior betrays only care and attention, would be quite shocked at the assertion that through lack of sufficient exercise more likely than not, she was untidy within.”

“Exercise generates force in the nerve centres, and these are the true source of perfect strength and beauty. A veneering of all the cosmetics manufactured cannot give the tone and clearness of colour, or radiance of expression to the face that a healthy body can give. Proper poise, to be gained through right exercise, is more conductive to a good figure than the most expensive corsets.”

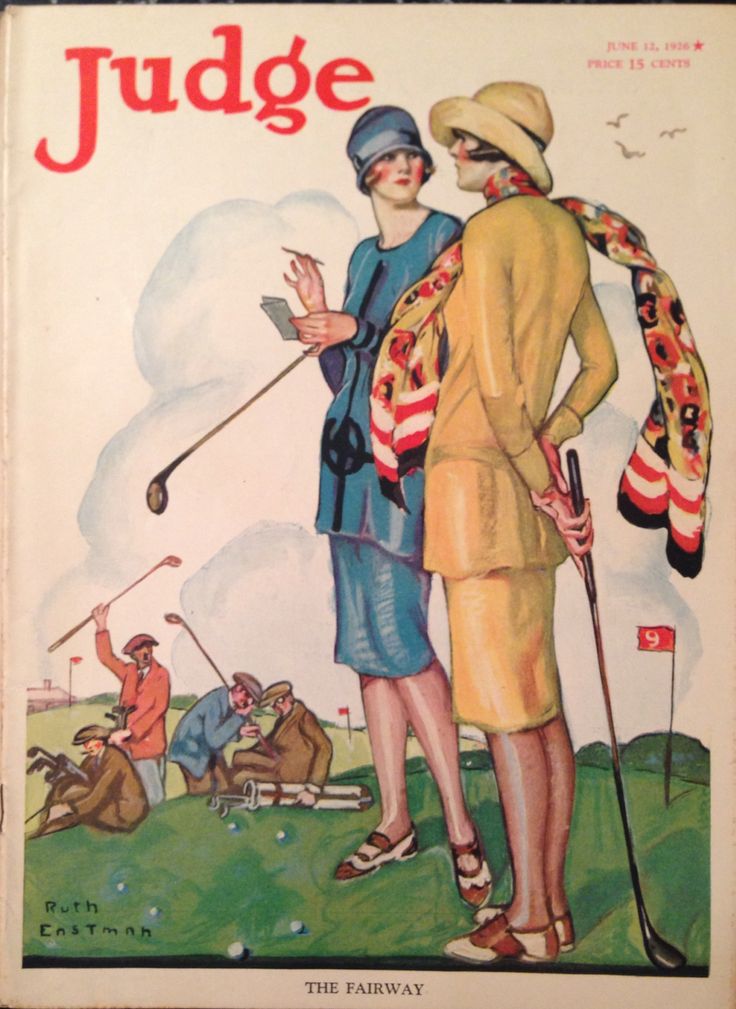

The interest in healthful living that ignited after the turn of the century continued to grow and had reached fruition by 1920. Love of physical culture had come to stand for a good deal. It is natural that if one possesses a body admirably proportioned, or graceful, or tall and slender, or supple, one may well take more pride in it than in any dress. A woman in a golfing costume was regarded as just as beautiful as in any more complicated toilette.

In April 1923, Mildred Manly Easton wrote the following in her monthly column, “Living a Balanced Life” in Woman s World Magazine: “The purpose of the body beautiful is to serve the cause of life, by serving you — a personality – in order that you may attain to your full stature of beautiful womanhood; and approach somewhere near the pattern image of perfection, stamped within; as the ideal fruit is stamped in the seed of the tree from the beginning.”

A reduction in the number of working hours, improvements in education, and easier and affordable travel all contributed to the amount of time available for intellectual pursuits. Time to reflect and improve oneself is a new luxury. The other influence on society is less subtle and decidedly more fun. Motion pictures.

The actors we watch on the silver screen wear beautiful clothes, know how to behave in every situation and project a casual confidence and elegance that is wholly new in the world. This is not the exclusive, aloof sophistication of the upper classes in the Victorian and Edwardian eras.

The gentleman today has an easy charm and humor that has nothing whatsoever to do with a family history back to the Crusades. This new man is appealing for many reasons; chief among them is that the sophistication he projects is born out of confidence in his abilities and accomplishments; not those of his ancestors.

Celia Caroline Cole describes a modem, worldly wise woman in an article for The Delineator: “She has insight — that woman — a fine selectiveness, an intuitive rightness. She has an eerie, sensitive something that always says and does and picks out the right thing. Her insight and judgement are subtle things underneath the skin. What you see is a calm, unhurried, sureness. Her appearance in clothes that emphasize a long, slim line is much like what is inside her: no excess of anything.”

By 1922 elegance and simplicity became synonymous. A woman who is one of the exponents of simplicity is obvious to the observer, for her ensemble is entirely free from all exaggeration. Simplicity as a fashion was definitely established, set up as a principle to which all the elegancies of apparel were actually subjected. Now, simplicity stood for the height of sophisticated refinement, an indication of the last thing in modernism. This simplicity meant simplification of exterior line and the reduction of the bulk of women’s clothing.

Changes in situation and the taste for travel by automobile aided in affecting simplicity in women’s dress. A large — quantity of complicated, voluminous clothes demanded a considerable staff of attendants. Such an abundance, at home or when traveling, necessitates a great deal of space in both places and this was no longer possible or desirable.

In learning to drive, women granted themselves an independence hitherto unknown. Automobile travel puts one in much closer proximity to one’s environment than travel by train or steamship. In getting out and seeing their world up close, women added to the general mood of the times.

This article was first presented in a longer version at Deco Days at the Awahnee in Yosemite National Park on Sunday, March 16, 2003.

Leave a comment