Keeping Your Cool: Mid-Victorian Sheer Dresses

by Elizabeth Urbach, First published for the May/June 2012 issue of Finery

Mid-Victorian daytime fashion was not all about heavy, opaque fabrics; warm weather allowed for light dresses of semi-transparent fabric like barege and muslin, trimmed with embroidery, ribbons and lace for a cool, floating visual effect. These gowns, called sheer dresses or “clear muslin dresses” were especially popular at the seaside and tourist resorts, during the 1840s through the 1870s. They were worn for morning, afternoon and evening, according to the bodice style, and were popular in England and North America. They followed the lines of mainstream fashion, but included features such as shorter sleeves, partial bodice linings, and depending on the sheerness of the top fabric, separate colored under-dresses. This article will focus on day or afternoon styles for sheer dresses.

Godey’s Lady’s Book of June 1852 describes the style in this way: “For baréges, Organdy muslins, or, indeed, thin tissues of any kind, Miss Wharton has adopted the ‘infant waist;’ a belt slightly rounded behind and before, scarcely more than a slope, indeed; the slight fullness of the waist has perhaps three shirrs, drawn with fine cord; the lining is cut out at the throat. … A collar, pointed in style, and of slight depth, is attached to the open corsages of older ladies. Small bishop sleeves, with cuffs, are used for morning-dresses … [and] the ordinary pagoda, or loose sleeve, is still in use for thin dresses.”

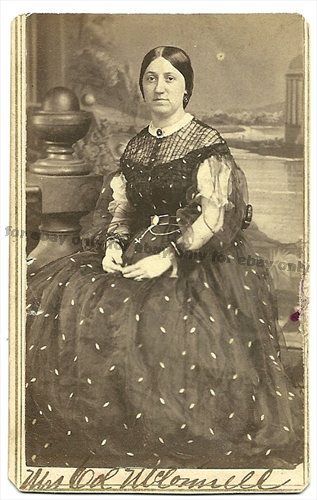

Most surviving sheer dresses are made of cotton or silk, but light wools were available and widely used. Fabric textures included both crinkled and smooth, plain-weave and gauze, and sheer to semi-sheer. Most sheer gowns shown in period photographs appear to be a solid white or black, but occasionally a print, or scattered floral embroidery is seen. Surviving garments are in solid white, tan, and black, as well as woven-in stripes and windowpane checks, embroidered spots and flower sprigs, and printed designs in colors such as brown, light to medium blue, lilac, and even red and black, on light backgrounds.

Plain white with no applied trim, or simply whitework embroidery, seems to be most common on extant garments, while plain black seems most common in period photos and daguerreotypes, although Godey’s and Peterson’s fashion magazines from 1859 through 1861 mention sheer evening dresses of blue and pink grenadine, organdie and barege. White or light sheer bodices were always lined in white, and black lined with black, but unlined black dresses are seen in period photos over either white or black petticoats. I could find no indication that sheer black dresses were confined to women in mourning. According to Kay Krewer on The Sewing Academy forum, “the only advice I’ve seen in period magazines is that older women should no longer wear white when the bloom of youth has left their cheeks!”

Fashion fabric necklines could be either high, with a jewel neckline or even a standing collar; low, from shoulder to shoulder in a straight line (especially in the 1840s); or mid-level, with a square or shallow V-neck shape. With the high or mid-level necklines, the bodice lining underneath stopped some 4 or 5 inches below, to leave a single sheer layer of fabric covering the décolletage. Sleeves on these bodices were generally elbow, ¾ length or full length, most commonly in a loose bishop or pagoda style, and lined no further down than the elbow. The sleeve lining could be no more than a short “jockey” underneath the sheer, longer sleeve. Waistline fitting treatments included loose gathers, knife pleats, tucks, and darts, with center-front smocking, gathers and fan-fronts more popular in the 1840s and ‘50s, and darts more popular in the late ‘60s and ‘70s. Pointed and round waistline shapes are both seen on these gowns, as are either front or back openings. Round waists either have set-in, self-fabric waistbands, or are covered with a belt or ribbon.

More surviving garments and period photos show the bodice and skirt attached to each other, although there are surviving garments and period images that show sheer bodices and skirts that are separate. Separate “basque” bodices with peplums are also seen in the early 1870s. The skirts of these dresses were most often left unlined, with a deep (5 to 8 in.) hem of self-fabric. With extremely sheer fabric, as seen in photos, a black or white “nice” petticoat, or under-dress, was worn underneath to show through, but fashion magazines suggested women consider a colored under-dress with a sheer white dress, especially for dressy wear. Skirts were either left single (plain, unflounced), trimmed with wide self-fabric flounces (1840s and 1850s), or narrower self-fabric ruffles and applied self-fabric ruching and bands (1860s and 1870s). Single-color ribbon banding as skirt trim was occasionally used.

Self-fabric ruffles, ruching, shirring, decorative tucks, knife pleats, whitework embroidery, and delicate lace, especially white “blonde” lace were most common trimmings. Ribbon colors run more to the pastels than the brights, although Godey’s Lady’s Book of September 1860 describes a “dress of clear muslin” trimmed with “[a] ceinture of green ribbon, with flowing ends, fastened in a bow on one side. The sleeves consist of four puffs of muslin, separated by rows of green ribbon. … The skirt is [trimmed with a] full and deep flounce, … edged with green ribbon, and disposed in the form of a festoon,” and the Victoria & Albert Museum has a ca. 1869 white cotton muslin dress that is trimmed with apple-green satin ribbon and self-fabric ruffles! I have not seen any sheer dress trimmed with embroidered or printed ribbon, or ribbon of more than one color.

To re-create your own sheer muslin dress, you can use the same pattern for both bodice and lining, and just cut out the top of the lining neckline and the bottom of the sleeves, or use two separate patterns. Jennifer Rosbrugh, in her article “Mid-Victorian Sheer Dresses,” says “it wouldn’t surprise me if women used their ball gown bodice pattern as the base for a sheer dress, then mounted the sheer bodice over it,” and there’s no reason why modern seamstresses can’t do the same thing and cut their bodice lining from a dart-fitted, mid- Victorian ballgown bodice pattern. For the sheer fashion fabric, you’ll need a gathered, fan-front, or darted mid- Victorian bodice pattern with a high to medium-high neckline, or one of the historic patterns now available which are specifically for sheer dresses. These include Truly Victorian’s #456 “1856 Gathered Dress”, Period Impressions’ #454 “Sheer Summer Dress” and #449 “1853 Fan-Front Bodice”, Past Patterns’ #812 “Sheer Muslin Dress”, #701 “1850-1867 Gathered and Fitted Bodices” or #801 “Fan Front Bodice”, and Laughing Moon Mercantile’s #114 “Ladies’ Round Dress” which has a sheer bodice option.

In making up your sheer dress, you’ll want natural-fiber fabrics that are sheer to semi-sheer, either lightly crinkled or smooth, and crisp instead of drapey. Heirloom-sewing fabrics are ideal, and don’t forget Shabby Chic-style window curtains; Target sometimes carries white cotton sheers with embroidered dots under the Shabby Chic brand name, that are a good approximation of 19th century spotted muslin. Look for silk or cotton batiste, cambric, lawn, nainsook, dimity, voile, organdy, organza, and seersucker or crepe plissé. If you can’t afford 100% natural fiber, then choose a rayon blended with cotton or silk, and the more natural fiber in the blend, the better, both for accuracy and warm-weather comfort! Avoid eyelet or lace yardage, although a late 1860s/early 1870s style sheer dress, made in plain white, can feature broderie anglaise insertion and flounces, or white beading with colored ribbon run through, like an original in the Metropolitan Museum of Art Costume Institute. With a muslin dress, you’ll look and feel cool at the Fallon House picnic or other summer Victorian event!

Leave a comment