Completing the 1912 Evening Look

by Kendra Van Cleave, First published for the March/April 2012 issue of Finery

In the early 1910s, women’s hair began with thick, wavy hair that was “dressed” in loose, “Grecian” styles. Wavy hair was desired, specifically the kind of wave that comes from thoroughly brushing out curly hair. If your hair did not have a natural wave, it would generally be curled through rag or pin curls. The “Marcel wave” (also called finger wave), with its characteristic side to side wave, was popular, although it was worn fluffier than the flat style typical of the 1920s-30s. Marcel waves were created through an artificial process using heated curling irons, and could last for up to a week.

Once the hair was waved, it was arranged loosely around the face and sides of the head, and then styled into a large bun, knot, or other arrangement at the low back of the head –“flat at the front, wide at the sides and full in the back” (Home Needlework, 1909). Numerous magazines of the era mention that fashions in millinery led hair styles; while hats were not worn in the evening, the style of the hair was the same. The Home Needlework Magazine wrote that, “The new hats are made to set down well upon the head, consequently the rolls and puffs are placed lower on the back of the head or nape of the neck, and the hair built out at the sides” (1909). Similar accounts of “lower” styles, being contrasted with earlier Edwardian pompadours, continue through 1912.

Because popular styles required so much hair, more than most women naturally have, hair “rats” (false supports for hair) and “switches” (lengths of human hair) were popular. Rats, made of wire, horsehair, and other non-human hair materials, were generally shaped as a long roll in a horseshoe shape that could be worn from ear to ear. They were worn underneath the hair, to fill out the style. When buying false hair, one could buy loose hair as well as curls, “puffs” (loose curled rolls of hair), braids, and styled chignons. According to the Millinery Trade Review, “false hair… is really quite in demand and the majority of women find it more convenient… the heads that wear bought hair look better coiffured than those that are natural” (1911). For modern costume wear, rats and false hair/hairpieces can be bought from many wig shops.

The most specific popular hair style was the “Psyche knot,” whose variations included: a bunch of curls or puffs that stood out from the back of the head; the same, but with a few drooping curls (recommended for young women); 4-5 puffs placed vertically at the base of the head; puffs encircled by a braid (recommended for matrons); a braid lying either on top or below a series of puffs; and many other variations. Cutting-edge trends for hair included the addition of bangs, and/or short curls around the ears and nape of the neck.

An excellent guide to early 1910’s hairdressing is the book Beauty Culture: A Practical Handbook on the Care of the Person, Designed for Both Professional and Private Use, published in 1911. It includes images and directions for numerous hairstyles, false hair pieces, and more. The entire book can be read online at Google Books: http://books.google.com/books?id=qmBFAAAAYAAJ More hair styling instructions from 1911 can be found at http://www.arrayedindreams.com/the-gilded-frock/girls-own-annuals/girls-own-paper-hair-lessons/

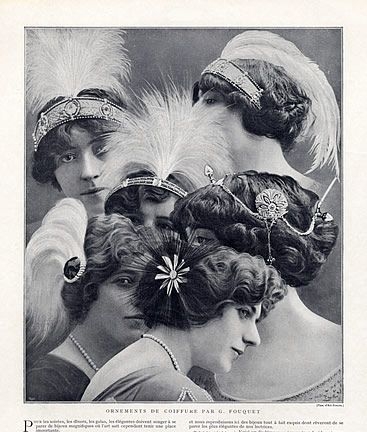

One of the most characteristic aspects of women’s evening coiffures in this era was the addition of hair ornaments. Plumes, flowers, jewelled ornaments and combs, and bands were frequently worn. Bands could be between one to four inches wide; with one, two, or three strands worn from ear to ear or around the head; and made of metal, velvet, or lace.

The 1910s was a transitional era in cosmetics wear. Many women wore powder and natural rouges in the nineteenth century, but it was considered very important to not appear to be wearing cosmetics because your physical appearance was believed to be a reflection of your inner moral character. Women who wore “paint” were thought to be trying to hide some inner moral flaw, and the only women who wore obvious makeup were actors or sex workers. However, the growth of advertising and shopping led to cultural changes whereby women were increasingly encouraged to literally create their identity through their appearance and use of consumer products. By the early 1910s, magazines were commenting that stylish Parisian women were wearing evident cosmetics, including eye makeup. For Americans, understated makeup began to be considered acceptable, although it was the trendsetting and/or “fast” women who were its first adopters, and in 1912 Elizabeth Arden founded her salon in New York City where she sold rouge and tinted powders.

To create an early 1910s upper class evening look with cosmetics, the following products can be used: powder to create a flawless, pale look; pink cheek rouge; eyebrow pencil; and lip tint made of colored salves (colored lip balm would be an excellent modern product). Very artistic women or those who are French might add smoky kohl around the eyes in a Theda Bara “vamp” style.

A woman’s evening ensemble was rounded out by numerous accessories. Shoes were made of silk satin, silk brocade, or kid leather, with one or more straps across the vamp that fastened with a button. Most shoes had around a 2.5” heel. Silk stockings were worn with evening ensembles. Popular jewelry styles included pendant necklaces, multiple strands of pearls, and chokers; drop earrings; rings; and cuff bracelets. Finally, small handbags were carried, made of leather or fabric on metal or ivory frames.

Leave a comment