Cavaliers and Rakes: Fashions of the Courts of Charles I and Charles II

by Gailynne Bouret, First published for the JulyAugust/ 2012 issue of Finery

Two periods in the Seventeenth century marked a departure from the old into the new: that of Charles I (1600-1649), the era of the Cavalier; and that of his son, Charles II (1630-1685), the Restoration. The fashions of these two eras reflect the personalities of each monarch. One manifested elegance; the other presaged the evolution of men’s dress into the modern suit.

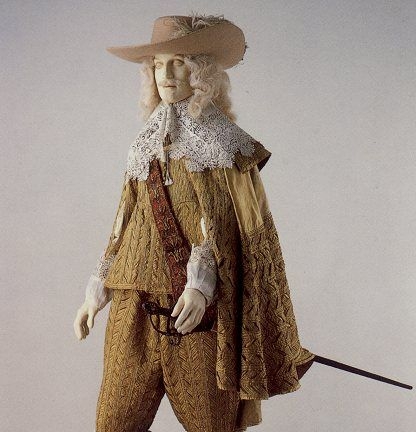

Charles I was a shy, reserved man. His court was noted for restraint, ushering in a new decorum based on protocol and ceremony. Portraits of Charles reflect a mixture of the kingly with the elegant. A transition from the Jacobean to Carolinian eras is seen in this portrait from 1631. The doublet is not stuffed and exaggerated, but has the new raised waistline and decorative slashes on the front. The doublet evolves in this decade from the overstuffed belly-piece of the Jacobean period with its short tabs to a higher waistline. By the mid-1630s, the doublet became more relaxed. There was no waist seam and it was worn open from mid-chest down.

Sleeves were loose and slashed throughout the 1630s. Sleeves opened from the wrist to the elbow and closed by buttons, or ended at the elbow in a turned-back cuff, revealing the full shirt sleeve.

Collars were high. The most common neckwear was the falling band collar. The band was made of starched linen or lawn, turned down over the shoulders forming an inverted V-shape at the throat. This band increased in size, broadening across the shoulders, throughout the coming decade. Sleeve cuffs matched the neck band.

The stiffly padded, short breeches of the early 17th century were replaced by long-legged breeches that hung loosely from the high waist and tapered down to the knees. They fell over the stockings, much like modern shorts. They were full in the seat and shaped to the man’s figure. A center vent, again like today’s trousers, was closed with buttons. The breeches were fastened to the doublet by points.

Stockings were heavily embroidered and tailored; knitted hose of wool or silk came into general use. Boot hose, made of linen, were worn over stockings to protect the thinner inner stocking. The tops of the boot hose were decorated and turned over the top of the boots.

Boots were made of soft leather and were close fitting, lined in linen. If thigh length, they were fastened to the breeches by points.

If thigh length, they were fastened to the breeches by points. They were stiffened on the inside but allowed to fold around the ankle. The lace inside the boot top often contained pockets for carrying personal items. Men’s shoes at this time were low-topped with a variety of heel heights and decorated with ties, rosettes, or bows.

Cavaliers were known for their shoulder-length hair, cut asymmetrically with one side below the ear and the other sporting a long lock tied with a ribbon, known as a love-lock. Upper class men used perfume, make-up, and face patches, and often dyed and curled their hair. The curling mustache and pointed beard, as worn by Charles I, became fashionable. But after the death of the king in 1649, beards were outmoded. The mustache, however, continued in style, attenuating into a thin line above the upper lip until its disappearance by the 1670s.

Finally, how can we not speak of the Cavalier period without describing its iconic hat? It began as a high-crowned hat with a flat or rounded top. In the 1630s, the brim became wide and cocked. Throughout the Carolinian era, the crown rose and fell, but the decoration of an ostrich feather or two was constant. With the advent of the Interregnum under Cromwell, however, the shape remained relatively the same, minus the vanity of feather and tilted brim.

With the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660, there was a reawakening of style, flamboyancy, and extravagance. Charles II had spent the twelve years since his father’s execution in exile at The Hague or in Paris. He was much influenced by the fashions of his cousin, Louis XIV, and the French court. It was an era where men outdid women in overdressing. The general effect of men’s clothing at this time was one of fantastic negligence, well suited to the moral climate of Charles’ court.

In the two decades preceding the restoration, the doublet lost the waist seam and became shorter. Although long coats were still worn at this time, “jackanapes,” or short-waisted coats, became extremely popular and often bordered on the ridiculous. Ribbons of all colors were fastened on the sleeves, at both the shoulders and cuffs. The short jacket revealed a good deal of cambric shirt, as did the short sleeves. Shirt sleeves were full and cuffs trimmed with lace frills. By the 1670s, the doublet was replaced by the coat and waistcoat. This “suit of vestment” is credited as being a forerunner of the modern suit. The coat was a loose garment that hung just below the knees, its skirt divided into back and side vents, allowing ease for riding. Sleeves lengthened through the era, ending in large, bulky cuffs. Nearly as long as the coat, the waistcoat buttoned completely down and concealed the breeches. While the coat was sometimes plain, the waistcoat was embroidered. Waistcoat sleeves were closer fitting and longer to allow for turning over onto the coat cuff, a fashion of the 1680s. The falling collar was replaced by the lace cravat.

Early Restoration breeches were wide-legged, pleated, and gathered into a waistband. Known as petticoat breeches or pantaloons, they fell like a divided skirt down to the knees. Like the jackanapes, petticoat breeches featured a multitude of ribbon loops at the waist or the sides. With the lengthening of the coat, full breeches became inconvenient. By 1690, breeches were plain and close fitting, gathered at the waist and fastened in the front.

Fashionable men wore silk stockings, gartered at the knee or above. With petticoat breeches, the cannons, decorative frills at stocking top, were turned down over the garter in a flounce. These often had bunches of ribbon or gathered lace at the top. This style went out of fashion by the 1680s.

Men’s shoes continued to have a high vamp and, by the 1640s, both shoes and boots featured a squared toe. Shoe rosettes were replaced with large bows of ribbon, sometimes wired out to either side of the foot. By the end of the century, these bows were replaced with buckles, a fashion that would continue into the 18th century. Both boots and shoes were predominantly black with red heels.

Finally, the most notable feature of Baroque fashion is the periwig. Following the fashion of Louis XIV, who began to wear wigs to cover his premature baldness, the periwig became a major fashion statement. The masses of curls fell on either side of the face and down the back. As a consequence, hats became wider, with larger feathers and additional ribbon trim. Soldiers found the full-bottomed wig cumbersome and wore “campaign” wigs that were bushy, with short curls at the sides and a short queue at the back. At home or in undress, men donned a bob wig. Despite the frivolity and inconvenience of wigs, they remained a fashion necessity for another century.

Whether an elegant Cavalier or a Restoration rake, the seventeenth century gentleman far outshone his female counterpart in style and ostentation.

Catherine J Berry

Thank you. This is exquisite.

Ms. Max

there’s a typo on the date of Daniel Mijtens portrait of Charles I above.

The text reads 1529. Charles I was born in 1600.