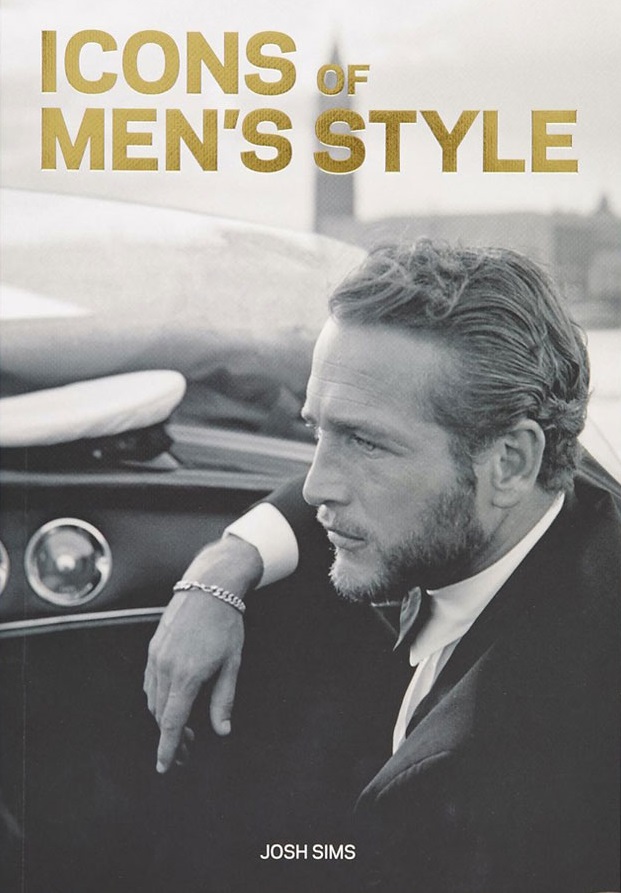

Book Review: Icon’s of Men’s Style by Josh Sims

by George McQuary, First published for the September/October 2012 issue of Finery

Since Beau Brummel, peacockery in men’s clothing has been shunned, innovation foresworn. The only changes in men’s clothing are in functional adaptations for industry, sports and military, which then slowly cross over into men’s fashion.

Take aviator glasses. Created to solve a certain set of industrial problems (pilot vision while operating a plane), their distinctive form stems from the functional problems they solve. They solved them so well that they were widely adapted by the piloting community, until ownership of the glasses became a secret sign to be read by other flyboys that you’re a member of their club too. But then to really become iconic, a fashion then has to break out of this secret club setting. Knowledge of it has to become so wide-spread that merely wearing it marks you as “one of those people”. And when the cultural waves hit just right, certain men’s clothing items ride the ridges until they are transformed into iconic.

This book is about those originals. The first cast from the mold that was so successful that all others evolved from it. And it documents them with photos.

Take the men’s biker jacket. Black leather. Wrapped up in bad-boy culture, rebellion, and some guy named James Dean. We all know it. We’ve all worn modern knock-offs. Wearing one is instant shorthand for a whole lifestyle, even philosophy. Drape it on your shoulders and suddenly people expect, even demand, certain behavior and attitudes from you. But what was the original that started it all, that became such a touchstone to our culture that even knock-offs are still resonating with its power today?

Josh Sims can tell you. It’s the Perfecto, made in 1928 by Russian Immigrant Irving Scott for Harley Davidson distributor Beck Industries. Other motorcycle clothing had been made before it. Those served their purpose and then went to the rag bin. But for some reason, the Perfecto took off, became embraced by a subculture, and became so tied to a certain image that it still is speaking today. Sims shows you the originals, rhapsodizes on specific details, and lets you know why this clothing still resonates.

Sims is strong when in the age of photography, brand names, and advertising. Venture before that and he becomes naive and too earnest–he repeats the official Brooks Brothers story that their button-down collar shirt innovation of 1900 came from a family member observing English polo field uniforms in 1896–one that men’s clothing historians have disparaged at least since the 1990s, largely with authentic photos of historical English polo clubs from 1896 without a single button on the collar tips in sight. Most now hold that the innovation was an American novelty that claimed (non-existent) English upper class origins to make it respectable to American middle class (but aspiring) consumers. But you want to know the first commercial pea coat? The first commercial blouson? Then Sims delivers.

It’s a fun read, thumbing through, seeing the originals, where they came from, why they were made to solve a distinctive problem, and how the power of solving that challenge through functional innovation while giving a distinctive look and feel gave them both a power and message still appeals to us today.

Men who enjoy mixing classics from the last 100 years into their modern wardrobe will find it a useful, and reasonably short, reference.

Leave a comment