Book Review: Elephant’s What?

by Betsy Hanes Perry, First published for the September/October 2010 issue of Finery

Elephant’s Breath and London Smoke: Historic Colour Names, Definitions, & Uses, edited by Deb Salisbury, is a sorely needed resource; anybody who’s spent time reading old fashion magazines has been frustrated by descriptions such as “a dress of serpent-gray silk”, which would have been transparent to the contemporary reader. (Or was intended to be; I suspect ladies outside the fashion centers were just as frustrated as we are.) The book does not cover as wide a period — 1380 to 1922 — as the back cover promises, but for the 18th and 19th centuries it is essential.

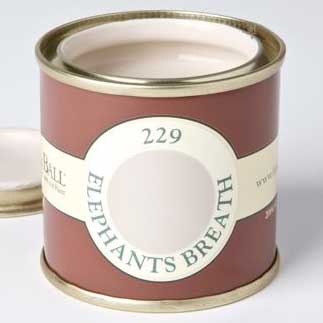

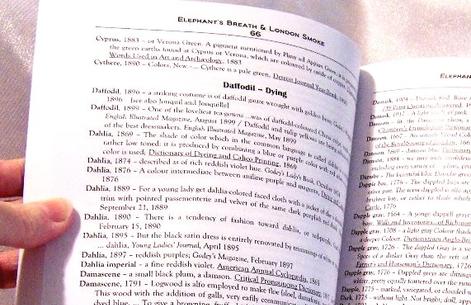

To begin with, Elephant’s Breath is fun. Just skimming the pages leads to treasures like “wine yellow: the pale and doubtful shade of claret known as wine-and-water”; and “clair de lune: A color that gives the effect of sheeny white, over pale blue.” I cannot overstate the pleasure of browsing this book. All citations are dated, so you can be confident that Schweinfurt Green (a brilliant sea-green), for instance, was in use both in 1835 and in 1870. Some citations contain only the name; most contain enough context to give you useful hints, at least, and often outright descriptions.

Editor Deb Salisbury draws on a wide variety of sources, not only the usual fashion magazines but also manuals for dyers, painters, and manufacturers. Including the latter was a brilliant decision, because manufacturers’ guides, unlike fashion guides, describe colors based on external, reproducible standards. For “fillemot”, a corruption of “feuillemort” (dead leaf), Johnson’s Dictionary (1792) merely says “a brown or yellow color.” The Dictionarium Polygraphicum (1735) describes how to dye fillemot in a series of yellow, black, and brasil wood baths. A dedicated historian could dye her own fillemot to get a good idea of the options.

Unfortunately, the book has some limitations. The back cover promises to cover “from around 1380 to 1922” in “English, American, Canadian, and Australian publications.” In practice, however, few of the citations are to sources from the 1600s or earlier. Most pre-19th-century citations are to 19th-century sources quoting or describing earlier sources; the Chaucer references are to an 1845 modernized edition of Chaucer. When I opened two pages at random, only two of the 18th-century citations were to 18th-century sources.

At the other end of the time scale, the references to early 20th-century sources are scant; the latest one I spotted was to 1910, and there are only a few 20th-century books in the bibliography. Finally, there are no references to modern scholarship — one obvious omission is Janet Arnold’s magisterial Queen Elizabeth’s Wardrobe Unlock’d. The author says frankly that “A great many of my sources were found on Google Books” and the book reflects the limitations of what is currently digitized and in the public domain. (If you consult the bibliography, however, the author has clearly researched many works that are not currently digitized.)

Almost all the citations about how color was used are to fashion publications. This is ideal for a costumer, but if you want to know what architects or interior designers were saying about colors you’re out of luck. There are invaluable citations to the 1908 Modern Pigments and their Vehicles, and to the 1834 Practical Treatise on Dying, both of which give recipes for colors, useful for pinning down precisely what was intended by a particular name.

Although the book is laid out in dictionary style, repeated references aren’t merged into a single head. Instead, you have eight definitions of “iron gray”, one after the other in a long line. Similarly, the entries for “dead leaf”, “feuille mort”, “filemot”, “foliomort”, and “philomot” are cross-referenced but not merged. It’s enormously labor-intensive to do this sort of merging, so for a single individual without the resources of an academic press, its absence is unsurprising.

There is enjoyable extended reading in the back under the title of “Period Comments on Colours” including “Victorian Complaints about 17th-Century Colour Names” and “Old and New Colours: 1872″. There is also an invaluable bibliography.

As a piece of scholarship, Elephant’s Breath & London Smoke has some limitations. For the nineteenth century, this book is indispensable; for the eighteenth, it contains much useful information; to research all other periods you should consult another work. And it’s a heck of an entertaining read.

Leave a comment