Gilded Age Outerwear

by Shelley Monson, First published for the November/December 2010 issue of Finery

The period known in America as the Gilded Age, roughly 1870 to the First World War, saw repeated radical changes in the silhouette of women’s clothing, moving through first bustle, natural form, second bustle, into the triangular shapes of the 1890s and the flowing curvilinear styles of the nineteen-oughts. The accommodation of the changing shapes of the skirt and sleeve were the governing force in the mutations of outerwear.

Throughout the period, the materials used to construct outer garments were mainly woolens, cashmere and velvets; silks other than velvets were sometimes also used, even including satin. Other fabrics included brocade, plush, alpaca, vicuña, sealskin, and matelassé. Trimmings were often elaborate, adhering closely to the current mode in dress decoration. Pleated trims, braiding, lace, ruching, jet beads, fringe, bobbles and fur edging were popular at various times; widows and other women in deep mourning of course trimmed their outer garments in crape.

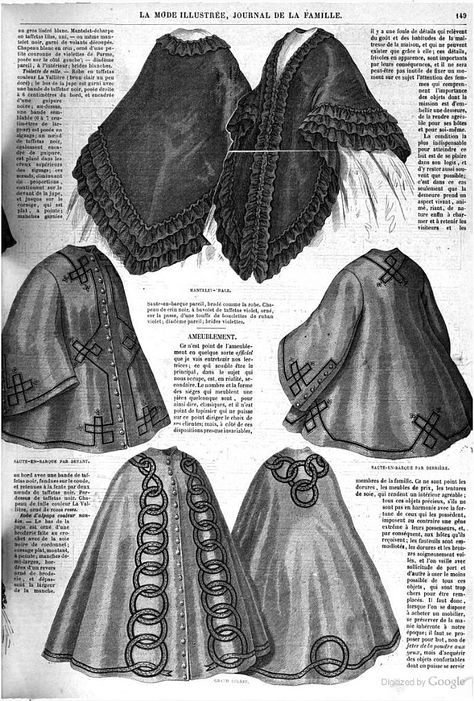

The terminology of outerwear in the 19th century is extremely confusing; the onlooker of the present day can see no difference between garments labeled “jacket,” “paletot,” “pardessus” or “visite.” The problem is exacerbated by the fact that the words change their meaning as time passes. Thus, I am well aware that whatever I say here, there will be examples found to disprove it! Additional confusion comes from the various permutations of the jacket- or coat-styled gown, which can easily be mistaken for outerwear. Generally speaking, jackets, visites and mantles were snug-fitting in the back but loose in the front, while a paletot was loose all around. A pardessus might be either. A casaque was snug all around. Needless to say, these are only generalizations, and all generalizations are wrong!

In the early 1870s we see the appearance of the term Dolman in outerwear; it is derived from the uniform of Hungarian Hussar troops. Initially, the term referred to a garment with loose cape-like sleeves, but toward the end of the 1870s, the sleeves become more closely cut, eventually pinioning the wearer’s upper arms completely. The modern meaning of a wide sleeve tapering to the cuff and cut in one with the body developed in the 20th century.

During the natural form period (approximately 1878-81), the lack of a bustle encouraged the use of long outer garments; during the two bustle periods, outerwear was most often long in front and short behind, or short all around. At the end of the ‘70s there was a revival of the fashion for Kashmir shawls; they had been very popular during the mid-century, but had fallen out of favor. In the ‘80s this vogue took the next step by using Kashmir and Paisley shawls as the material to make Dolmans and other mantles.

The 1880s also saw the introduction of the tailor-made costume, after which fashion divided into two streams; the more mannish tailor-made styles and the elaborate artistic styles. Both were influenced in different ways by the dress reform movement. In the mid-‘80s there was a vogue for Hussar and Zouave jackets, brought on by the Egyptian campaign for the relief of General Gordon at Khartoum. At this time mantles were generally black.

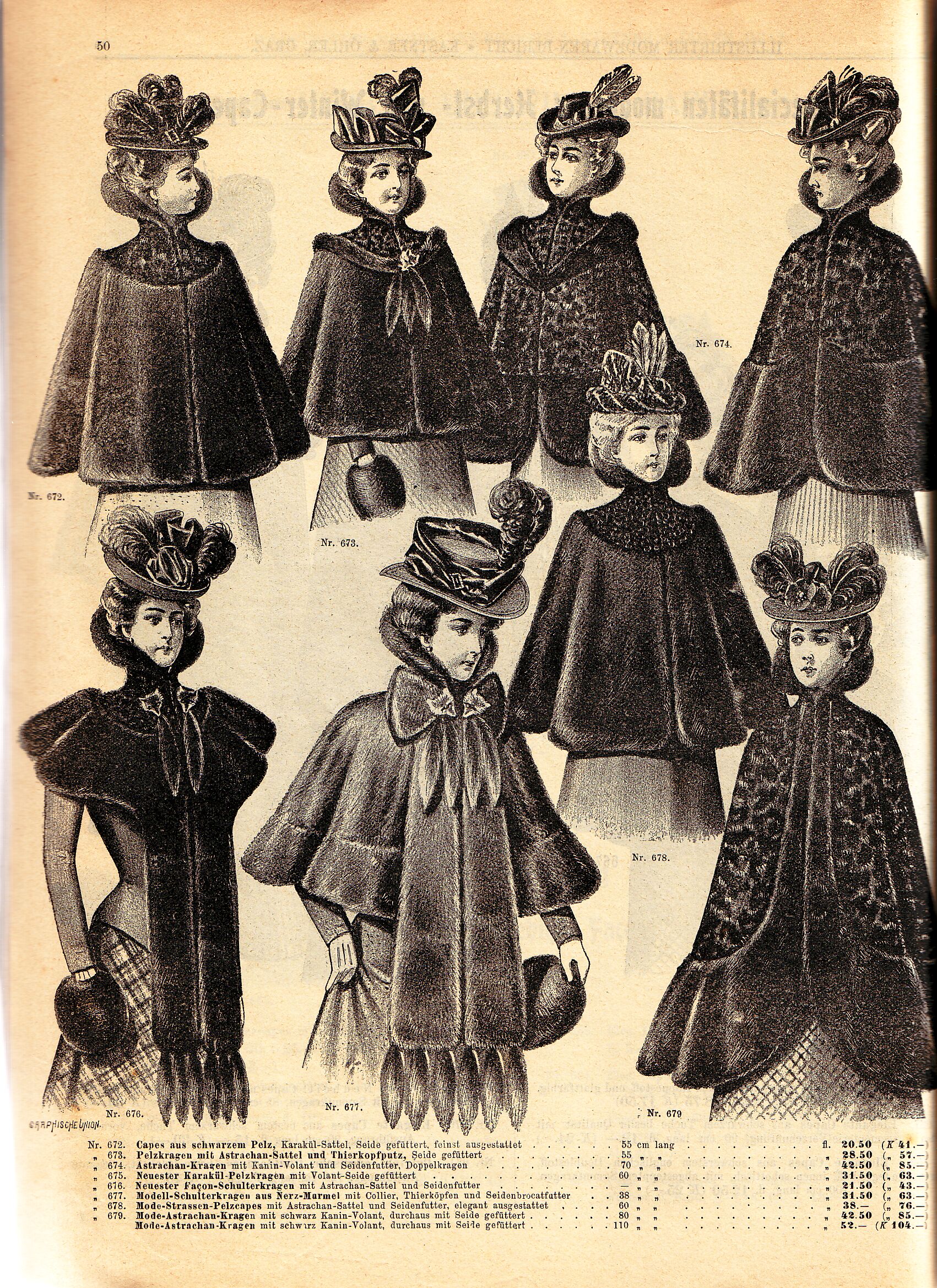

As the 1890s opened, all wraps except mantles were cut to fit the figure closely, and high collars were very popular. As the size of the dress sleeve increased, most outer garments tended to have no sleeves at all, such as cloaks and capes, though some outer garments had still larger sleeves that the wearer had to negotiate their dress sleeves into, a proceeding fraught with difficulty. Burberry’s gabardine was a very popular fabric for outerwear during the ‘90s. A model seen frequently in the mail-order catalogs of the ‘90s was a jacket based on the traditional seaman’s pea-coat, cut straight in the double-breasted front, and fitted behind.

In the mid-90s, up until 1896, exaggerated size was a dominant theme; big butterfly bows on the shoulders and tremendous collars were prevalent in outerwear. In that year, the dress sleeve suddenly collapsed, retaining only a small puff at the shoulder. As a result, jackets came back into fashion – with butterfly bows under the chin, and still sporting high collars.

In 1897, there was a radical shift in fashion from the stiff, straight lines of the early ‘90s to a more flowing, clingy style. Outer garments became more fitted, though cloaks remained fashionable. This more graceful style continued through the earlier years of the 20th century.

Cloaks of various lengths were a perennial during the Gilded Age. Full-length cloaks had been fashionable in the ‘60s, and a variety that reached just to the upper arm was popular in the ‘80s and ‘90s. In 1887 full-length cloaks were revived, trimmed with fur at the edges. As the decade came to a close, Ulsters with waist-length shoulder capes and coachman-style cloaks with multiple shoulder capes became popular. Throughout the period, evening and opera cloaks were always fancier than day-wear, with finer fabrics and more elaborate trimmings.

The topic of bonnets and hats is a magnum opus in itself, but I would like to mention two other items of headgear. A cloud, also known as a fascinator, was a fluffy straight scarf worn loosely wrapped around the head; it was so light weight that it did not disarrange the coiffure. There were also various shapes of hoods, both knitted and quilted, which were worn for warmth.

Leave a comment